The northwest region of the Indian subcontinent is the site of the emergence of the Indus or Harappan culture.

Because it was first discovered in 1921 at the current location of Harappa in the state of west Punjab in Pakistan, this civilization is known as the Harappan civilisation.

The same cultural, historical, and geographical entity confined to the Indus valley is also known by the name Indus civilisation.

Image Source: 3219a2.medialib.glogster.com/media/18/187c4b304d7c7cfa7725fd9ee2f92742e304eee49357c17dc7718a7de08ee274/indus-valley-civilization-source.jpg

The word “Indus civilisation” was originally used by John Marshall, who was also the first person to use the term. The Indus Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, dates back to the Chalcolithic or Bronze Age. Objects made of copper and stone were discovered at a number of different sites associated with this civilization. There are over 1,400 Harappan sites known to exist across the subcontinent at this time.

The Harappan culture encompassed these people during its early, mature, and late eras. However, the number of places that belong to the mature phase is quite small, and of those, only a half dozen or so may be considered to be cities.

Some of the noteworthy sites which have been excavated are Harappa (1921) by Daya Ram Sahni, Mohenjodaro (1922) by R.D. Banerjee, Dholavira (1967-68) by J.P. Joshi and (1990-91) by R.S. Bisht, Kalibangan by Dr. A. Ghosh, Lothal (1955-63), Chanhu-daro, Banawali (1975-77), etc.

Origin and Evolution:

It seemed as though India’s oldest and earliest civilisation had suddenly arisen on the stage of history, fully formed and with everything it needed to function properly. The discovery of this civilisation posed a historical mystery. Up until very recently, there were no clear indications that the Harappan culture was ever born or growing.

Following the considerable excavation work that was carried out at Mehrgarh near the Bolan Pass between the years 1973 and 1980 by two French archaeologists named Richard H. Meadow and Jean Francoise Jarrige, the mystery was able to be solved to a significant degree.

They claim that the site of Mehrgarh provides us with an archaeological record that details a progression of occupations. Archaeological study conducted over the course of the past few decades has revealed a continuous series of strata, demonstrating the Indus civilisation’s slow but steady ascent to the high standards of a fully developed society.

These layers have been given the names pre-Harappan, early Harappan, mature Harappan, and late Harappan, which refer to different phases or stages of the Harappan culture. The beginnings of the Indus civilization can be discovered by first looking at the fundamental aspects of the agrarian cultures that existed on the Indian subcontinent. Any Pre-Harappan society that wishes to stake a claim to lineage in the Indus civilisation is required to fulfil both of the following prerequisites.

The first need is that it not only precede but also overlap with the Indus culture.

The second is that the Proto-Harappan (Indus) culture must have anticipated the essential elements of the Indus culture in their material aspects, namely the rudiments of town planning, the provision of minimum sanitary facilities, knowledge of pictographic writing, the introduction of trade mechanisms, knowledge of metallurgy, and the prevalence of ceramic traditions.

An investigation of four sites that mirror the chronology of the four main stages or phases in the pre-history and proto-history of the Indus valley region can trace the distinct stages of the indigenous evolution of the Indus.

According to the evidence uncovered at the first site, Mehrgarh near the Bolan Pass, the sequence begins with the shift of nomadic herdsmen to sedentary agricultural settlements. It continues in the second stage with the establishment of big villages and the rise of towns, as shown at Amri.

The Amri people had no knowledge of urban planning or writing. The third stage of the cycle begins with the creation of large cities such as Kalibangan and finishes with their decline, which is illustrated by Lothal. The Amri, Kot-Dijian, and Kalibangan cultures are pre-Harappan in stratigraphy.

Amalananda Ghosh, the excavator, refers to the pre-Harappan culture of Kalibangan in Rajasthan as Sothi culture. The Harappans owed the Sothi ware several aspects such as the fish scale and pipal leaf.

The four Baluchi civilizations, Zhob, Quetta, Nal, and Kulli, are unquestionably pre-Harappan, but they share certain minor characteristics with the Indus civilisation and cannot be termed full-fledged proto-Harappan cultures.

Northern Baluchistan culture is known as ‘Zhob’ culture, after the sites in the Zhob valley, the most important of which is Rana Ghundai. This culture is distinguished by black and red ceramics as well as terracotta female figurines. The use of white-clipped ceramics with appealing polychrome paintings and the practise of fractional burial distinguish Nal culture.

The buff-ware pottery of the Quetta culture is painted in black pigment and ornamented with geometrical motifs. Aside from painted themes like the pipal leaf and sacred brazier, certain ceramic shapes are shared by the Harappan and Kulli cultures. All of these pre-Harappan habitations prior to the Harappan civilization exhibit evidence of people living in stone and mud-brick dwellings.

Cultural traditions of the numerous agricultural cultures living in the Indus region during the ‘early Indus period’ shared similarities. These small traditions were merged into one large tradition throughout the urban age.

However, even during the ‘early Indus period,’ the usage of identical types of pottery terracotta mother goddess, representation of the horned deity in various sites point to the emergence of a homogeneous tradition throughout the region.

Baluchistanis had previously established trade links with places in the Persian Gulf and Central Asia. Kulli, located on the Makran coast in the southern foothills of the Baluchi mountains, is an important stop on the trade route connecting the Persian Gulf and the Indus Valley.

Thus, the evidence implies that the Harappan culture originated in the Indus Valley. Several civilizations appear to have contributed to the evolution of urban civilisation even inside the Indus valley. There is no evidence that the Indus people borrowed anything significant from the Sumerians. As a result, Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s assertion that “the idea of civilization came to the Indus valley from Mesopotamia” is difficult to believe.

Date and Extent:

Between the years 2500 and 1800 B.C., a culture known as the Harappans flourished in India. Between 2200 and 2000 B.C. was when it reached its full maturity. The development of radiocarbon dating has made available a fresh pool of data that can be utilised in the process of establishing the Harappan chronology. The Indus civilization was the most extensive cultural zone of its time, covering an area that was significantly larger than that of any other contemporary civilisation at the time (about 1.3 million square kilometres).

Over a thousand locations have been found up to this point. It stretches from Ropar, virtually impinging onto the sub-Himalayan foothills in the north, to Daimabad in the Ahmadnagar district of Maharashtra in the south, and from Sutkagendor (on the sea-coast of south Baluchistan) in the west to Alamgirpur (in the upper Ganga-Yamuna Doab, U P.) in the east. All of these locations can be found in India.

Characteristics of Indus Valley Civilisation:

1. Indus Valley Cities:

The excavated Indus cities may be classified into the following groups:

(i) Nucleus cities

(ii) Coastal towns

(iii) Other cities and townships.

I. Nucleus Cities:

(a) Harappa:

It was the first Indus site to be discovered and excavated in 1921 by Daya Ram Sahni. The site has two large and imposing ruined mounds located some 25 kms. South-west of Montgomery district of Punjab (Pakistan) on the left bank of river Ravi.

The vast mounds at Harappa were first reported by Masson in 1826. Alexander Cunningham identified Harappa with Po-Fa-to or Po-Fa-to-do visited by Hiuen-Tsang.

a) The western mound of Harappa, smaller in size represented the citadel, parallelogram in plan and fortified.

b) Outside the citadel was the unfortified town having some important structures identified with workmen’s quarters, working floors and granaries. The workmen’s quarters, 10 in number were of uniform size and space (17×7.5 m). Close to these quarters were 16 furnaces, pear- shaped on plan with cow-dung ash and charcoal.

c) 12 Granary building of 15.24×6.10 m each, arranged systematically in 2 rows (6 in each row) with central passage 7 m. wide

d) The material remains discovered at Harappa are of the typical Indus character, prominent being.

e) 891 seals which form 36.32 per cent of the total writing material of the Indus civilisation ,

f) Two very important stone figurines (not available at any other site) which include one red stone torso of a naked male figure (the prototype of the Jina or Yaksha Figure) and a female figure in dancing pose.

g) A crucible used for smelting bronze was also found at a slightly higher level.

h) Dog attacking deer on a pin

Evidence of the disposal of the dead has been found to the south of the citadel area named as cemetery R-37. Excavations have also yielded 57 burials of different types. The skeletons were disposed of in the graves along with the grave-goods.

(b) Mohenjo-Daro:

The site of Mohenjo-Daro (or the Mound of the Dead) situated in the Larkana district of Sind (Pakistan) and 540 km. south of Harappa is situated on the right bank of the river Indus. It also has two mounds, the western being the citadel or acropolis and the eastern extensive mound was enshrining the relics of the buried lower city. The mounds were excavated first by Sir John Marshall. The citadel was fortified with big buildings extremely rich in structures.

a. The most important public place of Mohenjo-Daro seems to be the Great Bath, with a bed made water tight by the use of bitumen and a system of supplying and draining away water. This tank which is situated in the citadel mound is an example of beautiful brick-work measuring 11.88×7.01 meters and 2.43 meters deep. Flight of steps at either end lead to the surface. There are side rooms for changing clothes. This tank seems to have been used for ritual bathing.

b. In Mohenjo-Daro, the largest building is the great granary which is 45.71 meters long and 15.23 meters wide and lies to the west of the great bath.

c. To the north-east of the great bath is a long collegiate building, perhaps meant for the residence of a very high official, possibly the high priest himself, or a college of priests.

e. The lower unfortified city displayed all the elements of a planned city. The remarkable thing about the arrangement of the houses in the city is that they followed the grid system with the main streets running north-south and east-west dividing the city into many blocks.

This is true of almost all Indus settlements regardless of size. The main streets in the lower city are about 9.14 metre wide. The drainage system of Mohenjo-Daro was very impressive. These drains were covered with bricks and sometimes with stone slabs. The street drains were equipped with manholes. Houses were made of kiln-burnt bricks as in Harappa.

f. Material remains of Mohenjo-Daro with its richness confirms that it was a great city of the Indus civilisation. About 1398 seals representing 56.67 percent of the total writing material of the Indus cities throws light on Harappan religion.

Important stone images found here includes the torso of a priest made of steatite (19 cm), lime stone male head (14 cm), the seated male of alabaster (29.5 cm), the seated male with the hands placed on knees (21 cm) and a composite animal figure made up of limestone. The bronze dancing girl from Mohenjo-Daro, considered a masterpiece (14 cm) is made by cast wax technique.

(c) Dholavira:

Situated in Kutch district of Gujarat, Dholavira is the latest and one of the two largest Harappan settlements in India, the other being Rakhigarhi in Haryana. The ancient mounds of Dholavira were first noticed by Dr J.P. Joshi but extensive excavation work at the site was conducted by R.S. Bisht and his team in 1990-91.

It shares almost all the common features of the Indus cities but its unique feature is that there are three principal divisions (instead of two in other cities), two of which were strongly protected by rectangular fortifications.

The first inner encloser hemmed in the citadel (the acropolis) probably housed the highest authority and second one protected the middle town meant for the close relatives of the administrators and other officials.

The existence of this middle town, apart from the lower town, is the unique feature of this settlement. The access to these fortified settlements at Dholavira was provided through an elaborate gate-complex.

(d) Kalibangan:

Situated in Ganganagar district of Rajasthan on the southern bank of the Ghaggar river this site was excavated by B.B. Lai and B.K. Thapar (1961-69). This site also has two mounds yielding the remains of a citadel and lower city respectively. Excavations have revealed evidence of pre-Harappan and Harappan culture.

a. The citadel and the lower city both were fortified.

b. The citadel had mud-brick platforms having seven fire-altars in a row.

c. The lower fortified town had two gateways.

e. The people of Kalibangan used mud-bricks for the construction of houses, the use of burnt bricks has been found only in wells, drains and pavements.

f .The cylindrical seals found at Kalibangan had an analogy in the Mesopotamian counterpart. The discovery of inscribed sherds clearly suggests that Indus script was written from right to left.

g. Excavations at Kalibangan revealed the evidence of the ploughed field.

II. Coastal towns

(a) Lothal:

It was an important trading centre of the Indus civilisation and situated near the bed of the Bhogavo River at the head of the Gulf of Cambay in Gujarat. Lothal was excavated by S R. Rao which brought to light five period sequences of cultures. It was one rectangular settlement surrounded by a brick wall. Along the eastern side of the town was a brick basin, which has been identified as a dockyard by its excavator.

a) The house of a wealthy merchant yielded gold beads with axial tubes and sherds of Reserved Slip Ware related to the Sumerian origin indicating that the merchants were engaged in foreign trade.

b) Metal-workers, shell ornament makers and bead-makers shops have been discovered here.

c) The discovery of the Persian Gulf seal and the Reserved Slip Ware suggests that Lothal was engaged in the maritime activities.

(b) Sutkagendor:

Situated at a distance of 500 kms to the west of Karachi on the Makran coast it functioned as a trading post of the Harappans. It was originally a port of Harappan according to archaeologist Dales but later cut off from the sea due to coastal uplift. Excavation at the site revealed the two-fold division of the township into ‘citadel’ and ‘Lower city’.

(c) Balakot:

Situated at a distance of 98 km to the north west of Karachi this coastal settlement yielded the relics of the pre-Harappan and Harappan civilisation. Baked bricks were used in few drains but the standard building material were the mud-bricks.

(d) Allahdino:

The excavations at Allahdino were undertaken by W. A. Fairservis and are situated at a distance of 40 kms to the east of Karachi. These coastal cities have yielded the remains of mud-brick structures.

III. Other cities and township:

(a) Surkotada:

Situated about 270 km. north-west of Ahmedabad in Gujarat the settlement pattern of Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and Kalibangan was repeated here. As at Kalibangan, both the citadel and the lower town were fortified. There was also an inter-communicating gate between the two.

In addition to mud- bricks, stone rubble was liberally used for construction. In the last phase of this site, bones of horses, hitherto unknown, have been discovered.

(b) Banawali:

Situated in the Hissar district of Haryana it was on the bank of the river Rangoi, identified with the ancient bed of Sarasvati River. The excavations conducted by R.S. Bisht have yielded two cultural phases, Pre-Harappan and Harappan, similar to that of Kalibangan.

The Harappan phase showed significant departure from the established norms of town-planning (chess-board pattern as in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, etc.). The roads were neither always straight, nor are they cut at right-angles. It lacked systematic drainage system, a noteworthy feature of the Indus civilisation.

(c) Chanhudaro:

The township of Chanhudaro, situated about 130 km. south of Mohenjodaro, consists of a single mound divided into several parts by erosion. An evidence of material remains clearly shows that it was the major centre of production for the beautiful seals.

The hoards of copper and bronze tools, castings, evidence of the crafts like bead-making, bone items and seal making suggest that Chandhudaro was mostly inhabited by artisans and crafts-men. Excavations have also unearthed a furnace with a brick- floor used for glazing steatite beads.

(d) Kot Diji:

Situated on the left bank of the Indus River about 50 km. east of Mohenjo-Daro, the site of Kot Diji excavated by F.A. Khan Yields two cultural phases’ pre-Harappan and Harappan civilisation. Material remains discovered at the site are terracotta bulls, five figurines of the Mother Goddess and large unbaked cooking brick-lined ovens.

2. Polity and Society:

There is very little information available regarding the political structure of the Harappans. If the cultural zone associated with the Harappan civilization and the political zone are considered to be the same thing, then the subcontinent did not see the formation of such a vast political unit until the Mauryan Empire. The Harappans are credited with carrying out the very first experiment of its kind, which involved the peaceful consolidation of the political unity of the diverse geographical groups that comprised the civilisation.

The complete absence of religious or political civil strife inside Indus state territory is illuminating with regard to the state’s capacity for peaceful administration. It is erroneous to believe that priests controlled in Harappa, as they did in the cities of lower Mesopotamia, because there are no religious structures of any type in Harappa, with the exception of the Great Bath.

3. Social set-up:

An important characteristic of the Indus civilisation was its urban life. The rural areas not only supported but often contributed to the socio-cultural development. The social stratification is reflected in the dwellings and disposition of the dead bodies in the graves.

4. Dress, Hairstyles and Ornaments:

The men of the Harappan civilization wore robes that exposed one shoulder, and the upper classes’ clothing was typically intricately patterned and decorated. Long hair was popular for both men and women, and beards were commonplace.

The extravagant headdresses worn by the Mother Goddess were most likely inspired by the celebratory apparel worn by wealthier women at the time. The women wore a skirt that was knee-length or shorter, and it was held in place by a girdle that consisted of a string of beads.

Pigtails were a common hairstyle choice among the women, similar to how they are worn in India now. The women’s hairstyles were frequently intricate. The women cherished their jewellery and accessorised frequently with chunky bangles, chunky necklaces, and earrings. Mirrors made of bronze were found everywhere. It would appear that the women who lived at Mohenjo-Daro were familiar with the application of collyrium, face paint, and other forms of makeup. Lipsticks were used, according to the findings of Chanhudaro. For shaving, men used a variety of bronze razors in their own grooming rituals.

5. Amusements:

Kids played with terracotta toys such as rattles, birds shaped whistle, bulls with movable heads, monkeys with movable arms, figures which ran down strings, the favorite being the baked clay cart.

Dice was used in gambling, marbles of jasper and chert were played by rich children. Music and dance were secular. Hunting and fishing was in vogue. On a few seals, hunting of wild rhino and antelope are shown.

6. Religious Practices:

We have not discovered any cult artefacts or temples at any of the Harappan sites, with the exception of the fire altars that were discovered at Kalibangan. On the basis of the material remains that have been discovered at numerous Harappan sites, we are able to conclude that the people of Harappa practised many aspects of later Hinduism. These aspects include the worship of the Mother Goddess, Pashupati Siva, animal worship, tree-worship, and other similar practises.

Mother Goddess was considered to be the most important female divinity. Figurines made of terracotta were discovered at Harappa, and one of them depicts a plant sprouting from the womb of a woman. There is a good chance that the image depicts the goddess of the soil. Because of this, the Harappans revered the earth as a goddess of fertility and considered her to be a deity.

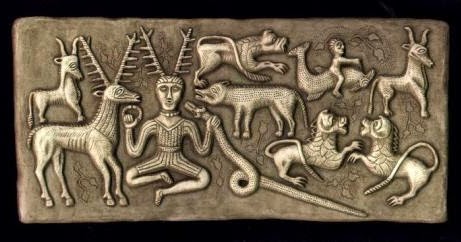

The horned-deity of the seals was the most prominent deity in Harappan society, and he was worshipped by the seals. On the first two, he is seen sat on a little dais, while on the third, he is shown sitting on the ground; in all three depictions, his stance is that of a yogi, sitting with his legs crossed in front of him. On the largest of the seals, he is encircled by four wild animals: an elephant, a tiger, a rhinoceros, and a buffalo, and beneath his feet are two deer. Each of these animals has a different colour and pattern.

Marshall boldly referred to this god as Proto-Siva, and the name has been universally accepted ever since. There is no doubt that the horned god shares a lot in common with the Siva of later Hinduism, who, in his most significant role as a fertility deity, is known as Pasupati, the Lord of Beasts. Certainly, the horned god has a lot in common with the Siva of later Hinduism. The worship of phallic deities was an essential part of the Harappan religion.

There have been numerous discoveries of artefacts in the shape of cones, which probably certainly constitute formalised representations of the phallus. In later forms of Hinduism, the phallic emblem known as the linga is considered to be the sign of the god Siva. The people who lived in the Indus Valley were also known to worship trees. A portrait of a god is depicted on a seal in the middle of the branches of a pipal tree, which is still venerated to this day. The seal was found in an ancient temple in India.

Animals were also venerated, and representations of many different species can be seen on ancient seals. The humped bull takes the cake as the most significant of these. Because of this, the people who lived in the Indus region worshipped gods that took the form of trees, animals, and even human beings. A significant number of amulets have been discovered. It seems likely that the Harappans had a belief in ghosts and other malevolent powers.

7. Burial Practices:

Cemeteries excavated at several Indus sites like Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan, Lothal and Ropar throws light on the burial practises of the Harappans. Three forms of burials have been found at Mohenjo-Daro, viz., complete burials, (means the burial of the whole body along with the grave goods) fractional burials, (burial of some bones after the exposure of the body to wild beasts and birds) and post-cremation burials.

From the Lothal cemetery comes evidence of another burial type with several examples of pairs of skeletons, one male and one female in each case, buried in a single grave. Bodies were always placed in the north-south direction with the head in the north.

8. Economy:

The Harappan economy was based on irrigated surplus agriculture, cattle rearing, proficiency in various crafts and brisk trade both internal and external.

I. Agriculture:

The Harappan villages, mostly situated near the flood plains, produced sufficient foodgrains not only to feed themselves but also the town people. No hoe or ploughshare has been discovered, but the furrows discovered in the pre-Harappan phase at Kalibangan show that the fields were ploughed in Rajasthan in the Harappan period.

The Harappans probably used the wooden ploughshare. We do not know whether the plough was drawn by men or oxen. Stone sickles may have been used for harvesting the crops. Gabarbands or nalas enclosed by dams for storing water were a feature in parts of Baluchistan and Afghanistan, but channel or canal irrigation seems to have been absent.

The Indus people produced wheat, barley, rai, peas, etc. They produced two types of wheat and barley. A good quantity of barley has been discovered at Banawali. In addition to this, they produced sesamum, mustard, dates and varieties of leguminous plants.

At Lothal and Rangpur, rice and spike- lets were found embedded in clay and pottery. The Indus people were the earliest people to produce cotton. Because cotton was first produced in this area the Greeks called it Sindon, which is derived from Sindh.

II. Domestication of Animals:

Although the Harappans practised agriculture, animals were kept on a large scale. Oxen, buffaloes, goats, sheeps and pigs were domesticated. The humped bulls were favoured by the Harappans. From the very beginning dogs were regarded as pets.

Cats were also domesticated. Asses and camels were used as beasts of burden. Camel bones are reported at Kalibangan. Evidence of horse are also reported from Mohenjodaro, Lothal and Surkotada. Elephants and rhinoceros were well known to the Harappans.

III. Technology and Crafts:

The Harappan culture belongs to the Bronze Age. The people of Harappa used many tools and implements of stone, but they were very well acquainted with the manufacture and use of bronze. Bronze was made by the smiths by mixing tin with copper.

Numerous tools and weapons recovered from the Harappan sites suggest that the bronzesmiths constituted an important group of artisans in the Harappan society. Objects of gold are reasonably common, silver makes its earliest appearance in the Indus civilization and was relatively more common than gold. Lead, arsenic, antimony and nickel were also used by the Harappan people.

The axes, chisels, knives, spearheads, etc., were made of bronze and stone. They seem to have been produced on a mass-scale in place like Sukkur. Two short copper swords found in Mohenjodaro are of the slashing type and not cutting type.

As for craft specialization, the towns of Chanhudaro and Lothal have yielded evidence of the presence of workshops of bead-makers. Balakot, Lothal and Chanhudaro were centres for shell-working and bangle- making.

Apart from them the evidences indicate the presence of potters, stone masons, brick makers, seal cutters, traders, priests, etc. The Harappans also practised boat making. Weavers wove cloth of wool and cotton. Spindle whorls were used for spinning. The potter’s wheel was in full use, and the Harappans produced their own characteristic pottery, which was made glossy and shining. Most of the time it means the use of a pinkish pottery with bright red slip and standard representation of trees, birds, animals and geometric motifs, in black.

No human figure is depicted on the pottery from Mohenjo-Daro but a few pottery pieces discovered from Harappa portray a man and a child. The Harappan pottery was highly utilitarian in character with artistic touch.

The greatest artistic creations of the Harappans are the seals. About 2000 seals have been found, made of stealite, these seals range in size from 1 cm to 5 cm. Two main types are seen. First, square with a carved animal and inscription and second, rectangular with an inscription only.

Stone sculptures and terracotta figurines have been reported from various sites. Figurines made of fire-baked clay, commonly called terracotta which were either used as toys or objects of worship. It was used mainly by the common people and it represented sophisticated artistic works.

9. Trade:

The importance of trade in the life of the Indus people is attested not only by granaries found at Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and Lothal but also by the presence of numerous seals, uniform script and regulated weights and measures in a wide area. They did not use metal money. Most probably they carried on all exchanges through barter.

In return for finished goods and possibly food grains, they procured metals from the neighbouring areas by boats and bullock-carts. Inter-regional trade was carried on with Rajasthan, Saurashtra, Maharashtra, parts of western Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Foreign trade was conducted mainly with Mesopotamia or Sumeria (modern Iraq) and Iran.

Their cities also carried commerce with those in the land of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Discovery of many Indus seals in Mesopotamia and evidence of imitation by the Harappans of some cosmetics used by the urban people of Mesopotamia suggests that some of the Harappan merchants must have resided or visited Mesopotamia.

About two dozen Indus type seals were also discovered from different cities of Mesopotamia like, Ur, Susa, Lagash, Kish and Tell Asmar. Reciprocal evidence comes from the Indus cities also-discovery of a circular button seals which belongs to a class of Persian Gulf seals, several bun-shaped copper ingots of Mesopotamian origin and the ‘Reserved Slip Ware’ of the Mesopotamian type at Lothal.

All these provide conclusive proof of trade links between the two civilisations. The Mesopotamian records from about 2350 B.C. onwards refer to trade relations with Meluha, which was the ancient name given to the Indus region, and they also speak of two intermediate stations called ‘Dilmun’ (identified with Bahrain on the Persian Gulf) and Makan (Makran Coast). Shortughai located near Badakhsan in north-east Afghanistan was one of the Harappan trading outpost, beyond the high passes of the Hindukush.

The Harappan cities did not possess the necessary raw material for the commodities they produced and hence depended upon the products imported from distant places. Main imports consisted of precious metals like gold (from North Karnataka), silver (probably from Afghanistan or Iran), Copper (from Khetri copper mines of Rajasthan, Baluchistan and Arabia), lead (East and South India), tin (Afghanistan and Hazaribagh in Bihar), and several semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli (Badakshan in North-East Afghanistan), turquoise (central Asia and Iran), amethyst (Maharashtra), agate (Saurashtra), jade (central Asia), and chalcedonies and carnelians (from Saurashtra and west India).

Main exports were several agricultural products and a variety of finished products such as cotton goods, carnelian beads, pottery, shell and bone inlays etc.

10. Weights and Measures:

The knowledge of script must have helped the recording of private property and accounts-keeping. Numerous articles used for weights have been found. They show that in weighting mostly 16 or its multiples were used; for instance, 16, 64, 160, 320 and 640.

The Harappans also knew the art of measurement. The measures of length were based upon a foot of 13.2 inches and a cubit of 20.6 inches. Several sticks inscribed with measure marks, one of these made of bronze have been discovered.

11. Script and Language:

The Harappans invented the art of writing like the people of ancient Mesopotamia. Although the earliest specimen of Harappan script was noticed in 1853 and the complete script discovered by 1923, it has not been deciphered so far. Unlike the Egyptians and Mesopotamians, the Harappan did not write long inscriptions. Most inscriptions were recorded on seals, and contain only a few words.

These seals may have been used by propertied people to mark and identify their private property. Altogether there are about 250 to 400 pictographs, and in the form of picture each letter stands for some sound idea or object.

The Harappan script is not alphabetical but mainly pictographic since its sign represent birds, fish, varieties of the human form, etc. and it was written from right to left like modern Urdu.

There are two main arguments as to the nature of the language; that it belongs to the Indo- European or even Indo-Aryan family, or that it belongs to the Dravidian family. Parpola and his Scandinavian colleagues gave a hypothesis that the language was Dravidian.

Problems of Decline:

In the absence of any written material or historical evidence, academics have speculated on the causes of the Harappan culture’s fall. Urban planning declined gradually in cities such as Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, and Kalibangan. Some of the settlements, such as Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, were later abandoned. However, most other places were still inhabited.

Some significant characteristics of the Harappan civilization, such as writing, standardised weights, pottery, and architectural style, vanished. Wheeler believed that the Aryan invaders annihilated the Indus civilization. It has been stated that there are evidences of a massacre in the late phases of Mohenjo-Daro.

However, it has been noted that Mohenjo-Daro was abandoned by around 1800 B.C., although Aryans are thought to have arrived in India around 1500 B.C. As a result, the notion of sudden death cannot account for the decline. Several academics agree with the progressive death theory.

R. Raikes, a hydrologist, has proposed that tectonic activity raised the flood plains of the lower Indus river, resulting in the lengthy submergence of cities like Mohenjo-Daro and Chanhudaro and their abandonment. However, the cause of the downfall of several other Indus cities, such as Kalibangan and Banawali, appears to be the drying up of rivers rather than floods.

W.A. Fairservis attempted to explain the decline of the Harappan civilization in terms of ecological problems. He believes the Harappans harmed their fragile ecology. A rising human and animal population, combined with diminishing resources, wore out the landscape, resulting in increased floods and droughts. These tensions eventually contributed to the breakdown of urban culture. The continuing fertility of the Indian subcontinent’s soils refutes this hypothesis.

According to E.J.H. Mackay, Lambrick, and John Marshall, the fall of the Harappan Civilization was mostly caused by the vagaries of the Indus River. However, Shereen Ratnagar of Jawaharlal Nehru University hypothesised in 1986 that lift-irrigation may have resulted in an over-reaching of its ecological limitations.

The Harappans are also thought to have had various suicidal tendencies. The Harappans, for example, lacked mental plasticity, as evidenced by the cities’ non-changing consecutive levels and their refusal to absorb Mesopotamian technological advances (iron technology). The Harappans also overlooked defence, as evidenced by the scarcity of sharp-edged effective weapons.

Although the eclipse of sea-trade may have contributed to the downfall of the Harappan civilization, it cannot be considered the primary cause. As seen above, there are various key explanations for the civilisation’s decline. Furthermore, there is ample evidence to suggest that the vast Harappan civilisation did not die suddenly, but rather withered away gradually.