Early Years:

In the sixth century B.C., Buddhism dealt the heaviest blow to Brahmanism. Gautam Buddha, a Mahavira-era contemporary, founded this faith.

He was a kshatriya and a member of the Sakya clan, whose dominion was represented by the region of Nepal directly to the north of the Uttar Pradesh district of Basti.

Suddhodhana, his father, was the head of the Sakya tribe at Kapilavastu.

Maya Devi was the name of his mother. She was a princess of the Koliyar, a nearby clan. He was created in 566 B.C. in Kapilavastu’s Lumbini garden. A week after his birth, his mother passed away. Prajapati Gautami, Siddhartha’s aunt and stepmother, raised him. After his aunt Gautami’s name, Siddhartha was then referred to as Gautama.

Education:

The “Lalitavistara” literature sheds light on Gautama’s upbringing. He developed his swordsmanship, riding, archery, and other royal skills.

Marriage:

Gautama displayed meditative tendencies since he was a young child. He was given numerous chances to live a comfortable and enjoyable life. He was raised in opulent settings so that he would be upbeat throughout the day. When Suddhodhana saw in his son a profound lack of interest in worldliness, he married him at the age of sixteen to Yasodhara, a stunning princess and the daughter of the Sakya noble Dandapani. Rahula, his son, was born to him when he was twenty-nine years old. But he had no interest in getting married.

He was troubled by the big issues in life, though. He was affected by the suffering that others endured and searched for a remedy. According to popular legend, Gautama was terrified to see an old man, a sick person, a dead body, and an ascetic.

He became aware of the hollowness of earthly pleasures after seeing these four sights. He was troubled by life’s essential issues. In a fit of renunciation in 537 B.C., he abruptly abandoned his wife, home, and son because he was drawn to the ascetic’s saintly aspect. in search of truth as a wandering ascetic at the age of twenty-nine. This event is known as the “Great Renunciation” in Buddhist literature.

He moved around aimlessly in pursuit of the truth. Alarkalam taught him the sankya doctrine in Vaisali. Leaving Vaisali, he travelled to Rajagriha. He studied meditation there under Rudraka Ramaputra. But he was unable to quench his need for knowledge with this yoga or meditation.

Then he travelled to Uruvila, which is close to Gaya, and started performing strict penance for an extended six years. But he came to understand that penance was not the right route that would provide him with absolute truth. So he made the decision to eat. A young milkmaid named Sujata gave him milk, and he took it. At Bodhgaya, he once bathed in the Niranjana River and then sat beneath a pipal tree.

After 49 days, illumination finally hit him. He gained the heights of wisdom and understanding. Since then, he has been referred to as the “Buddha,” the “Enlightened one,” or “Tathagat,” and this is known as the “Great Enlightenment.” The “Bodhi Tree” is the name given to the pipal tree where he obtained enlightenment. The location of his meditation became known as “Bodhagaya” at that point.

Turning the Legal Wheel

He maintained his joyful state of mind for his enlightenment for seven days. For the benefit of the suffering people, he made the decision to distribute it. He then travelled to the Deer Park close to Saranath, which is near Varanasi, where he gave his first sermon to five knowledgeable Brahmanas. It was referred to in Buddhist writings as “Turning the Wheel of Law” or “Dharma Chakra Pravartana.”

Buddha’s Missionary Activity:

He travelled extensively for the next 45 years, spreading his message to all corners of the globe. He travelled to Benaras from Saranath and won over many people to Buddhism. He left Benaras for Rajagriha, where he won the conversions of many notable individuals, including King Bimbisara, Prince Ajatasatru, Sariputta, and Maidglyana. He travelled to various locations, including Gaya, Nalanda, and Pataliputra.

He also travelled to Kosala, where Brahmanism was already established. Kosala’s King Prasenjit adopted Buddhism. His two sisters Soma and Sakula, as well as one of his queens Malika, became his pupils. Buddha resided in the Jetavana monastery there, which his wealthy follower Anathapindika had paid a significant sum to acquire for him.

During his visit to Kapilavastu, the Buddha also won over the family members of the resident, including his parents and son, to his way of thinking. Amrapalli, a well-known Vaisali courtesan, was converted to his faith. At Vaisali, the Buddha approved the creation of the Bhikshuni nun order. He had little success with the Malla and Vatsa nations. He avoided going to Avanti Desa. He did not differentiate between high and low, man and woman, or the affluent and the destitute.

In 487 B.C., on a full moon day of Vaisakha, he died at the age of eighty after preaching and giving sermons for a long forty-five years in Kusinara, modern Kasia in the Gorakhpur district of Uttar Pradesh. This event is referred to as “Mahaparinirvana” in Buddhist literature.

Buddha’s teachings

The Pali Suttapitaka, which consists of five Nickayar, is the earliest source of the Buddha’s teachings still in existence. Buddha was a reformer who observed life’s facts.

Four enduring truths

He advised following a set of practical ethics with a logical perspective. Buddhism was primarily a social movement. It promoted social justice. Buddha avoided getting involved in the debates over “Brahma” and “atman” during his lifetime. He gave more thought to global issues.

The Noble Truths of the Four:

He taught his adherents the following four “Noble Truths” (Chatvari Arya Satyani):

(1) That there is much suffering in the world

(2) That there are factors that contribute to suffering, such as thirst, desire, attachment, etc., that result in a material existence

(3) That the annihilation of thirst, desire, etc. can end suffering.

(4) The destruction of suffering is the route that leads to it.

The eightfold path

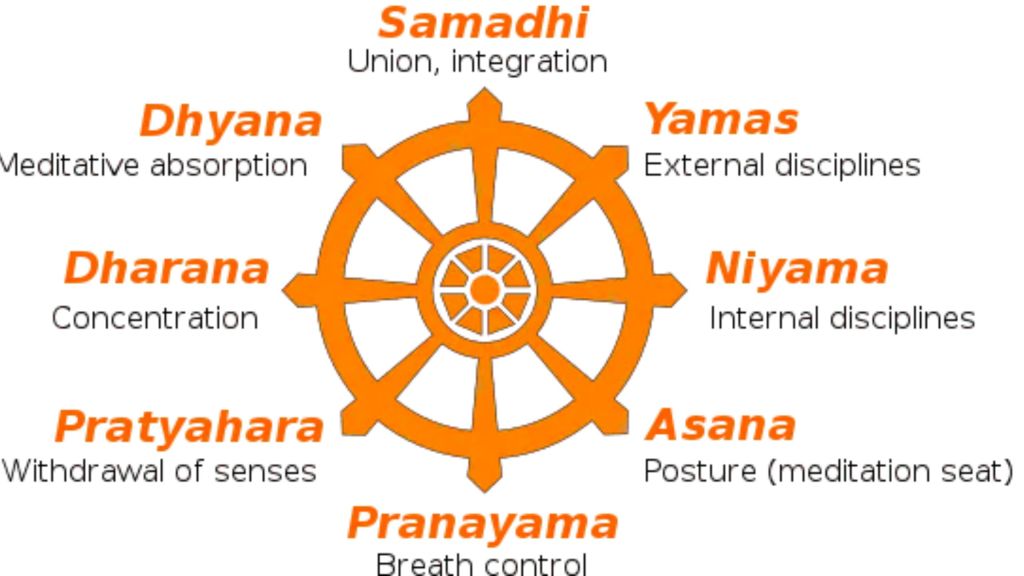

Buddha proposed the Eightfold Path (Arya Ashtanga Marg) as a way to be freed from suffering after detailing the series of causes that lead to suffering, specifically:

1) Correct speech

(2) Good deed

(3) Appropriate means of support

(4) Proper effort

(5) Good judgement

Six) Proper meditation

(7) Appropriate resolution

(8 ) Right angle.

The first three exercises result in Sila, or bodily control, the next three exercises result in Samadhi, or mental control, and the final two exercises result in Prajna, or the growth of inner sight.

Middle Road

The middle way is also known as the eight fold path. The life of ease and luxury and the life of extreme austerity are the two extremes it lies between. Buddha taught that this intermediate way ultimately leads to nirvana, or ultimate bliss. Nirvana literally translates as “blowing out” or the cessation of desire, craving, or trishna for existence in all of its manifestations.

It is a peaceful state that can only be attained by someone who is devoid of all want or desire. Nirvana is a perpetual state of serenity or happiness that is free from sorrow and longing (asoka), decay (akshya), disease (abyadhi), and birth and death (amrita). It is liberation from rebirth.

Buddha gave his followers a set of rules for conduct as well. These are referred to as the “Ten Principles,” and they include:

(1) abstain from violence

(2) Avoid stealing

(3) refrain from engaging in unethical behaviour

(4) Avoid lying to others.

(5) Use intoxicants sparingly

(6) Don’t utilise a cosy bed.

(7) Don’t go to dance and music events

(8) Avoid eating erratically

(9) Don’t accept gifts from others or desire their possessions.

(10) Avoid making savings.

One can live a virtuous life by abiding by these ten rules.

The law of karma

Buddha placed a lot of emphasis on the Law of Karma, how it operates, and soul reincarnation. He believed that a person’s state in this life and the next relies on his or her choices. Not any deity or gods, but man is the creator of his own destiny. One can never get away from the results of their actions. A man will be reborn in a higher life if he commits good deeds in this incarnation, and so on until he achieves nirvana. Evil acts will undoubtedly be punished. To experience the results of our past deeds, we are continually reborn. This is the Karma Law.

Nonviolence or Ahimsa:

Ahimsa is a key tenet of the Buddha’s philosophy. More significant than good deeds is the non-violent attitude towards life. He counselled against harming or killing other people or animals. The slaughter or hunting of animals was discouraged. He denounced eating meat and performing animal sacrifices. Even though Buddha placed a high value on non-violence, he allowed his followers to eat flesh when there is nothing else they can use to stay alive.

God:

Buddha does not affirm or deny the existence of God. When asked whether God existed, he either remained silent or said that Gods and gods were subject to the timeless law of Karma. He avoided engaging in any speculative dialogue concerning God. He was just interested in relieving man of his misery.

Against the Vedas:

The Vedas’ dominance was rejected by the Buddha. He rejected the value of intricate Vedic and Brahmanical ceremonies and practises for achieving salvation. He criticised the dominance of the Brahmans.

Against the Caste System:

The caste system or Varna order was denounced by the Buddha. He asserts that a guy should be evaluated on the basis of his character rather than his birth. All castes are equal in his sight. Because of his opposition to the caste system, he gained the support of the lower classes.

The Church of Buddhism:

As significant as the Buddha and his teachings was the Samgha, or Buddhist Church. All adults over the age of fifteen were eligible to join the Buddhist Church, regardless of their caste or class, as long as they were free of leprosy and other ailments. Women were permitted entry. A member of the sangha who wished to be ordained as a monk had to select a preceptor and get the approval of the other monks. The consent was obtained, and the convert was duly ordained. He was required to swear fealty to the Sangha leader. The oath read:

As in “Buddham Sharanam gachhami”

I seek solace in the Buddha.

As in “Dhamam Sharanam gachhami”

(I seek solace in the Dharma)

Singing “Sangham Sharanam gachhami”

(I seek safety in the Sangha)

The convert was initially allowed to lower ordination, or “pravrajya,” and after ten years of strict morality and austerity practise, he was subsequently promoted to higher ordination, or “Upasampada.” His life was governed by the Patimokkha after the disciplinary time was over, and he was admitted as a full member of the church.

The Development of Buddhism:

In contrast to Jainism, this religion sprang off like wildfire because it offered relief to a community that was overloaded by Bramhnical ceremonies and rituals. Many causes contributed to its proliferation.

- Buddha’s Perfect Life

Buddhism’s growth was aided by the Buddha’s character and the way he taught the faith. Many people were drawn to his teachings by his humble lifestyle, endearing words, and life of renunciation. He made an effort to combat bad with good and hatred with love. He constantly engaged his adversaries with intelligence and poise.

Vedic Religion’s Missed Opportunities:

The intricate rites, rituals, caste structure, animal sacrifices, etc. of Brahmanism made it complex. Brahmanism had grown to be very intricate and expensive, and the common people had had enough. Buddhism was more liberal and democratic than Brahmanism. The people felt relieved by the Buddha’s words. It was devoid of the negative aspects of Brahman.

Pali language usage:

The people who helped propagate Buddhism spoke Pali, the language that the Buddha used to communicate his teachings. Sanskrit was used to explain the Vedic religion. The average person has a hard time understanding it. However, Buddhism’s tenets became widely applicable.

Buddhist community:

Buddhism has expanded as a result of the Buddhist Sangha’s missionary efforts. Buddhism was only practised in Northern India during the Buddha’s lifetime and even after his passing. However, it became a global religion under the Mauryan dynasty because to the efforts of the Buddhist Sanghas, Monks (Bikshus), and Upasakar (lay followers).

In India, the Buddhist Sangha created its branches. In Mathura, Ujjain, Vaisali, Avanti, Kausambhi, and Kaunaj, monks disseminated the Buddha’s teachings. Buddhism was warmly received in Magadha since they were despised by the orthodox Brahmanas.

Royal Support:

Buddhism quickly expanded thanks in large part to royal patronage. Several monarchs, including Prasenjit, Bimbisara, Ajatasatru, Asoka, Kaniska, and Harshavardhan, supported the development of Buddhism both inside and outside of India by adopting various policies. For the purpose of promoting Buddhism, Asoka sent his daughter Sanghamitra and son Mahendra to Sri Lanka. Buddhism was able to travel the lengthy path of development and enter Tibet, China, Indonesia, Ceylon, Japan, and Korea thanks to the efforts of the kings.

Universities’ roles:

Buddhism was indirectly promoted thanks to the well-known Universities at Nalanda, Puspagiri, Vikramasila, Ratnagiri, Odantapuri, and Somapuri. Many of the students who read in these universities were impacted by and adopted Buddhism. Additionally, they disseminated Buddha’s teachings widely. Hiuen Tsang, a well-known Chinese pilgrim, attended Nalanda University. Shilavadra, Dharmapala, and Divakaramitra were just a few of the well-known instructors from Nalanda who committed their lives to the propagation of Buddhism.

Councils of the Buddha:

Additionally, the Buddhist councils were crucial in the development of Buddhism. In 487 B.C., the first Buddhist Council was held not long after Buddha’s passing. Ajatasatru directed the compilation of the Dhamma (religious theory) and vikaya (monastic discipline) in Sattaponi cave, close to Rajagriha.

The council was headed over by Bikshu Mahakashyap. At the council, which was attended by around 500 monks, the Buddha’s teachings were collected into the Sutta and Vinaya pitakas. They were penned in Pali, these two Pitakas. Two well-known followers of Buddha, viz. The council was addressed by Upali and Ananda.

The second Buddhist Council was held at Vaisali in 387 B.C., exactly 100 years after the death of Buddha, because a disagreement arose over the code of discipline as the monks of Vaisali and Pataliputra started to practise ten rules that were opposed by the monks of Kausambi and Avanti, including storing salt for future use, eating after midday, overeating, drinking palm juice and accepting gold and silver.

So, in 387 B.C., a council was called and presided over by Kalasoka or Kakavarnin. which criticised all ten of the regulations. The Vaisali monks’ conservatism caused the council to fail, which caused the Buddhist Church to split into staviras and Mahasamghikas. The latter were pro-changers, while the former adhered to the traditional vinay.

In 257 B.C., the third Buddhist Council convened. For the purpose of ending the split within the Buddhist religion and making it criminal, Asoka convened a meeting at Pataliputra under the direction of Moggaliputta Tissa. The concepts of the two pitaks that were already in existence were given intellectual interpretations by the council, which were said to be authentic to the original teachings of Buddha.

At Kundalvana Vihara in Kashmir, under the direction of Vasumitra and Asvaghosha, the Kushana King Kinaska called for the Fourth Buddhist Council. Three sizable comments on the three pitaks were compiled by the eminent Buddhist scholar Parsva. They’re referred to as Vibhashas. Asvaghosha was the founder of Mahayana Buddhism, a new school of Buddhism.

As a result, the Fourth Buddhist Council divided Buddhism into the “Hinayana” and “Mahayana” schools. The ultimate goal of life, according to the Hinayanas, was Nirvana, who saw Buddha as a wonderful man rather than a deity. The Mahayanas revered Buddha as a deity and followed the eight-fold path without placing much emphasis on achieving Nirvana. As a result, Buddhism became more well-known thanks to the efforts of the periodic Buddhist Councils.

Buddhism is dwindling:

By the twelfth century A.D., Buddhism had spread throughout India. A number of elements contributed to the decline of Buddhism in India.

Buddhist Sanghas’ decline

The demise of Buddhist Sanghas was a significant factor in the decline and fall of Buddhism. Sanghas became into hubs of corruption. There was a breach of vinay pitaka discipline. People who liked ease controlled the viharas. The nuns and monks started leading enjoyable lives. The Mahayanists and the Hinayanists fought one another. Buddhism turned out to be destroyed by internal struggle.

- Brahmanism returning:

The demise of Buddhism was also a result of the resurgence of Brahmanical Hinduism. Hinduism’s rites and rituals were streamlined. Additionally, it accepted Buddha as a Hindu incarnation and included the nonviolence concept of Buddhism. The Gupta emperors supported Brahmanical religion greatly and made significant contributions to it. People were drawn to the Brahmanical Hinduism that had undergone reform.

Buddhists are divided:

Buddhism eventually lost its originality as a result of being split up into other groups, including “Hinayana,” “Mahayana,” “Vajrayana,” “Tantrayana,” and “Sahajayana.”

Sanskrit language usage

The language of the common people, Pali, was abandoned by Buddhist monks. Buddhism’s growth was caused by the Buddha’s use of Pali in his sermons. Sanskrit, however, which was a language used by intellectuals and was rarely understood by the general populace, was adopted by Buddhist monks. People therefore rejected it.

Worship of Images:

The Mahayana Buddhists began to revere Buddha as a deity. This image worship was blatantly against Buddhist beliefs, which were opposed to important Brahmanical Hindu rituals and rites. Buddhism suffered a decline in popularity as a result of image worship because it gave the public the impression that Buddhism was being influenced by Hinduism.

Loss of royal support

As time went on, Buddhism lost the royal support it had under the reigns of Asoka, Kaniska, and Harshavardhana. Earlier, royal patronage had a significant role in the growth of Buddhism. But Buddhism came to an end as a result of the absence of royal support.

the rise of the Rajputs

From the eighth to the twelfth centuries, the Rajputs, who took great pleasure in battle, governed the majority of Northern India. They abandoned the nonviolence taught by Buddhism. They supported Hinduism, a militant religion. Buddhist monks fled Northern India because of fear of persecution. As a result, Buddhism all but vanished from Northern India.

Islamic Invasion

Buddhism in India was essentially killed off by the Muslim conquest. Muslim conquerors were drawn in by the wealth of the Buddhist viharas. Thus, Muslim invasions with the sole purpose of stealing the wealth turned their attention to the Buddhist viharas. The Muslim assault was too much for the Buddhist monks to handle.

Numerous Buddhist monks were murdered, others were converted to Islam, and others escaped to Nepal and Tibet where they sought refuge. Even though Buddhism originated in India, where it ultimately perished, it persisted for centuries in other countries.