What are the milestones that an individual must attain in order for their lives to be considered “well lived”? Humans have a habit of summarising someone’s life in a few words – she was a scientist, he was a martyr, she was a writer.

We record it on paper, assemble it in a book, and call it history. However, history is frequently forgotten. And with it, the people who formed our past and, in some ways, our future.

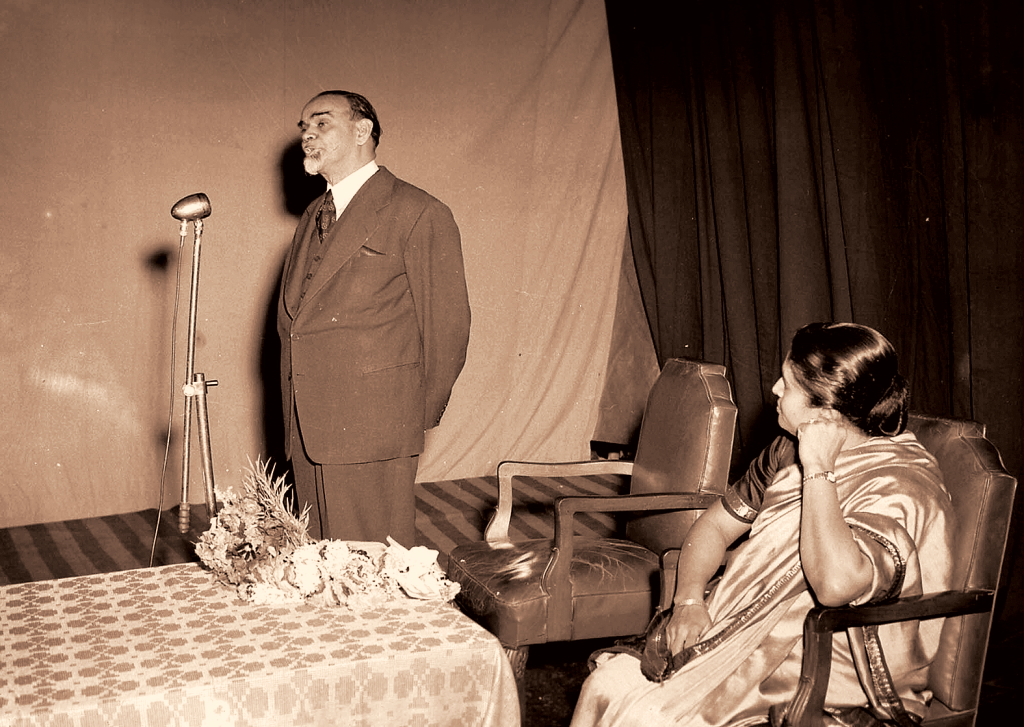

So when I googled Sardar KM Panikkar, it was clear to me that his work had faded with time as the pages of history turned. Upon further investigation, I discovered that these pages attempted to characterise him in a few words – “He was the first president of the Kerala Sahitya Academy.” But was he just another writer and admirer of poetry, or are we missing something?

A well-lived life

Panikkar was born to Puthillathu Parameswaran Namboodiri and Chalayil Kunjikutti Kunjamma in Travancore, then a princely state in British India. Panikkar, a multilingual writer, statesman, educationist, diplomat, journalist, and independent India’s first ambassador to China, is one of the most influential figures in defining contemporary India.

He worked as a professor at Aligarh Muslim University and afterwards at the University of Calcutta after finishing his schooling at Madras and the University of Oxford. Soon after, he found a new vocation as the editor of the Hindustan Times in 1925.

He was a historian at heart, and he wrote many volumes, including Malabar and the Portuguese (1929) and Malabar and the Dutch (1931). Jawaharlal Nehru endorsed his book Asia and Western Dominance, and Krishna Menon remarked, “He can write a history book in half an hour that I couldn’t write in six years.”

He was a lover of poetry and languages, and began writing Malayalam poetry in the Dravidian metre at a young age. He emphasised the significance of Dravidian languages to Indian civilization. He was elected as the first president of the Kerala Sahitya Academy in 1956.

Panikkar was a part of the first Indian mission to the United Nations after India’s independence, led by Vijay Laxmi Pandit. In 1952, he was chosen as independent India’s first ambassador to China, and then to Egypt.

His life seemed to be leading up to the point where he strategically saved at least a thousand migrants crossing the border during the Partition.

“Sardar” the man who saved thousands of refugees

When India attained independence, there was still hope for freedom, progress, and a better future. But what followed was a divided country and days of agony.

Panikkar chronicled his final days as Secretary to the Chamber of Princes in Bikaner before being asked to serve as Ambassador in his book In Two Chinas. “To the north and east of it (Bikaner) lay East Punjab, where Hindus and Sikhs had banded together against the Muslims and were murdering, looting, and setting fires.”

“To the west of it lay Bahawalpur in Pakistan, where five thousand Hindus were massacred in a single day,” he said, adding that the pandemonium on both sides resulted in a tremendous flood of Hindu and Sikh refugees fleeing Pakistan and arriving in Bikaner.

The Muslim population of Bikaner was also afraid. “They were terrified not of the refugees, but of the vengeful Sikhs who lived in nearby Ganga Nagar.”

Panikkar had resolved to take action in response to the circumstance. The human brain is capable of achieving inconceivable things in times of tremendous hardship. He made the decision to save those innocent people only out of humanity.

“I was well aware that if I did not stop the conflagration on the borders of Bikaner and prevent it from spreading, it could not be stopped and would reach as far as Bombay with consequences that no one could predict,” he recalled.

He was afraid of causing any communal strife in Rajasthan, where Muslim invaders have repeatedly attacked Rajput kingdoms while attempting to help Muslim refugees. But he decided to go ahead with it.

“I was determined at all costs to prevent the trouble spreading into Bikaner, not merely for humanitarian reasons, but because I was well aware of the consequences of arousing the dormant anti-Muslim feeling of the Rajputs, and I knew that if there was the slightest weakness on my part, Rajputana would repeat, perhaps in an exaggerated form, the terrible history of Punjab,” Panikkar writes.

With Maharaja Sadul Singh’s assistance, he dispatched the royal army to Ganga Nagar for inspection and issued a warning. The army was given orders to shoot the rioters, and civil authorities were given the authority to levy collective penalties on violent groups.

Despite these precautions, he was concerned that violence would erupt as tensions escalated in Punjab and New Delhi.

His pleas for assistance fell on deaf ears as the institution was overrun with refugees. He made the decision to take affairs into his own hands. “I decided to escort the refugees across the state, partly by special trains over the Bikaner State Railway and partly on foot across the sands of Bikaner,” he wrote.

The choice did not sit well with the unruly mob, but he had the Maharaja’s complete support.

The first convoy arrived in Pakistan with no one injured. “Taking courage, I then ordered a second convoy, this time on foot and with only a Police escort, to march across the state,” he wrote.

Thousands of women, men, and children walked the 350 kilometres across the desert. “When this weary procession also reached Pakistan, I heaved a sigh of relief,” Panikkar says in his book.

The diplomat’s life was forever changed by the Partition. He went to New York as part of India’s delegation to the United Nations General Assembly, which launched his career as an Indian diplomat.

He recalls Partition with “inhuman cruelty, deliberate massacres, and large-scale relapse into atavistic barbarism, which were displayed on both sides.”

Panikkar died of heart failure in 1963, while serving as vice chancellor at Mysore University. His daring act, however, left a great legacy.

So, ideally, the next time we read about him, history will remember him as the ‘Sardar’ who went to tremendous efforts to save something valuable — fellow humans.