As seen from Calicut, the Chinese navy emerged on the horizon, set against a scorching tropical sun, making for an impressive sight. Nothing could have prepared the astounded port authorities, the Arab Muslim trading community, the fisherman, or the locals who stood by the beach and saw the event that was taking place in front of them back in 1406 CE.

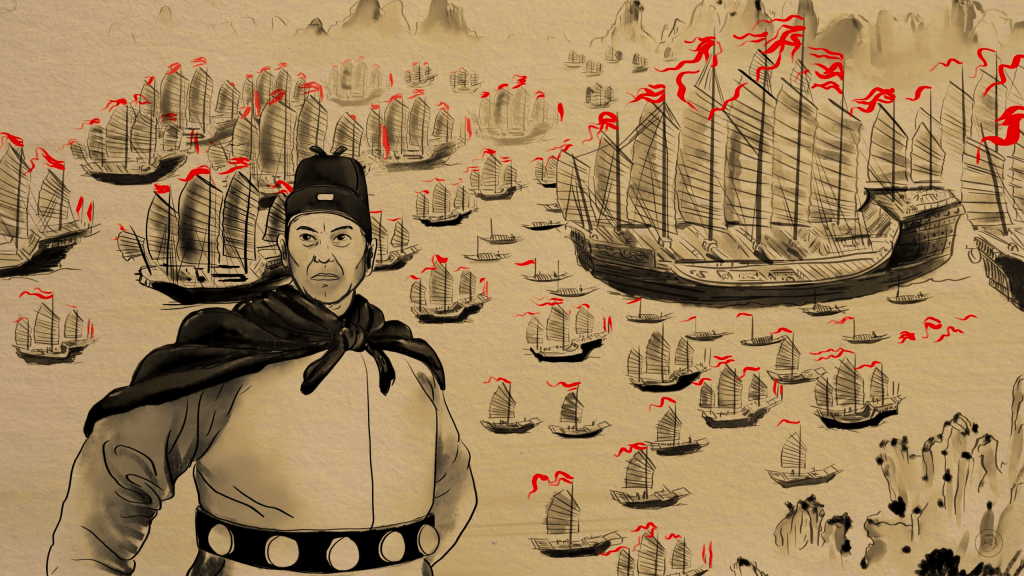

The fleet of stately Chinese junks, their white sails drawn taut against the monsoon winds, stretched miles across the horizon as they approached Calicut. The deadly warrior admiral Zheng He emerged from the front row boat that later landed ashore at a towering seven-foot height! The boisterous audience was quieted. Arriving was the imperial Chinaman!

Ancient cultural and commercial ties bind China and India together. Few people in India are aware that the famed Chinese admiral Zheng He (1371-1433 CE) visited Calicut (today’s Kozhikode) on many commercial expeditions in the early 15th century CE, despite the fact that the voyages of Chinese monks like Fa-Hein (399-412 CE) and Hiuen Tsang (630-645 CE) are well known. For our benefit, his scribe Ma Huan wrote a description of some of the visits and what he saw in this place. The Chinese admiral’s journey to Calicut was evidence of the long-standing tight ties between China and the Malabar ports on India’s west coast.

These connections go back to the time between 140 and 86 BCE, when envoys landed by sea at ports along South India’s east coast. Since then, ships from traders from Malaysia, Java, Vietnam, India, and the Arab world have fought for space in the South China Seas, leading to piracy as well as brisk trade and naval competition. Trade and relations persisted, but things started to shift after the port of Canton was reopened in 792 CE, when the Chinese pushed the Arabs to steer clear of western Asia and towards eastern Asia. The first trade ships from the Persian Gulf to reach Chinese ports were Chinese junks.

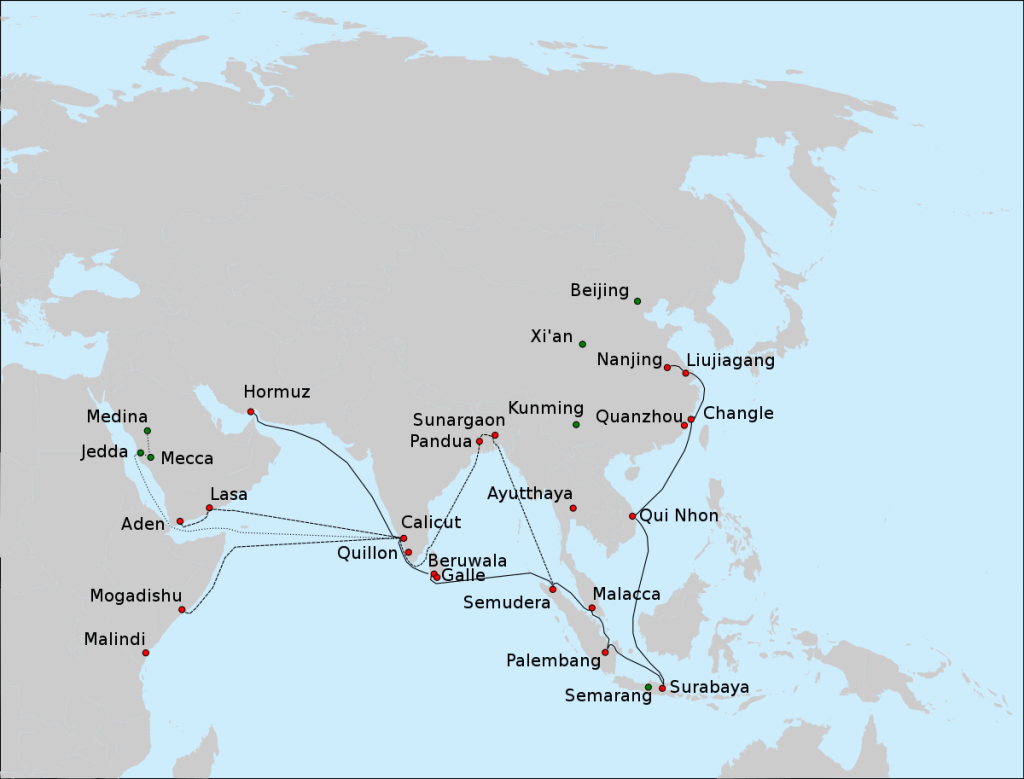

This trade between the Arabs and the Chinese was heavily dependent on the ports in India’s Malabar region. Ships going for China would use the monsoon winds to navigate their way through the Persian Gulf, pass from Muscat to Malabar, and then spend the final two weeks of December trading at Kulam Mali (the modern-day Keralan town of Kollam).

They would cross the Malacca Strait by January in order to go through the South China Sea during the southern monsoon. After spending the summer at Canton, the ship would travel back to the Malacca Straits with the northeast monsoon between October and December, cross the Bay of Bengal in January, and depart from Kulam Mali to the Gulf at the beginning of the next year. Definitely a long voyage!

Through the rule of the four great Chinese dynasties, namely the Tang (618-907 CE), Song (960-1229 CE), Yuan (1229-1368 CE), and the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE), Kollam and China maintained their trading relations. The farthest point west reached by Chinese ships up until the rise of the Ming dynasty was Kollam. As trade grew, the massively planked, multi-decked Chinese ships known as junks started to cruise towards South East Asia and South Indian coastlines. As a result, Kollam developed into a crucial port for transhipment in the Sino-Islamic trade, where mariners loaded cargo onto vessels bound for China to the east or the Arabian Peninsula to the west as they crossed the Arabian Sea, also known as the “Eastern Sea of the Muslims.”

The collapse of the Arabian Abbasid Caliphate empire in the middle of the eleventh century opened the way for the rising Turks. Since Kollam was closely associated with the Abbasids and heavily dependent on them as patrons, trade with the Persian Gulf decreased quickly. Two developments occurred at this time: first, trade was restricted as a result of China’s loss of coin currency, and second, Chinese, Jewish, and Syrian Christian traders and guilds were displaced at Kollam in favour of Karimi and Mamluk Arab traders. As a result, significant changes took place in Kollam as well as Malabar.

The new Karimis and Mamluk merchants were dislodging the established Persians, i.e. the Iraqi-Baghdadi traders and their local equivalents in Kollam. The majority of the Arab traders just relocated to Calicut since they had no desire for close ties with the Christians and Jews in Kollam and had noticed the rise of a Muslim-friendly Zamorin. Thus, Calicut’s fortunes greatly improved. The port of Kollam had so lost favour with Chinese authorities by the time the Ming Voyages under Zheng He set sail in the 15th century, while still being in use. The main commercial stops had relocated to Calicut around this time.

Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan adventurer who visited Kollam and Calicut in the period between 1341 and 1343 CE, wrote extensively about the superiority of the Calicut port. He made at least five trips to Calicut and documented the city’s environment as well as the thriving Calicut-China trade, giving considerable information about the several enormous Chinese junks berthed close to the Calicut harbour.

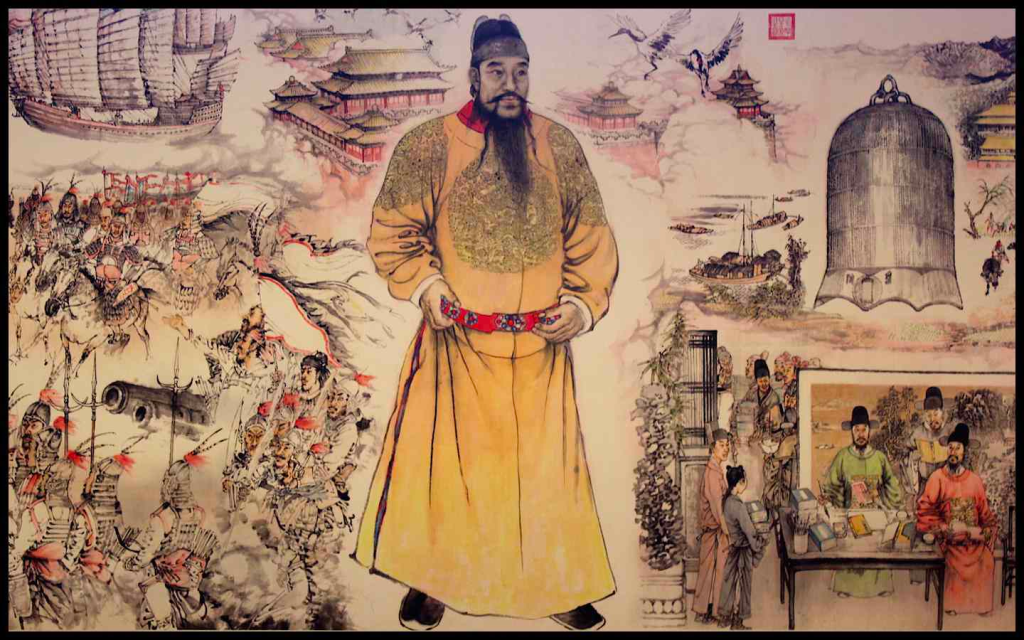

Chu Ti (Zhu Di) and his eunuch-supported army overthrew Emperor Chu Yen-Wen of China in 1399 CE, who luckily managed to flee. When General Zheng He (Zheng He) was seized from the Mongol troops, castrated, and enlisted in the Ming Army in the 1380s, he first became acquainted with Chu Ti. He was a large, commanding man who was heavily active in the Chu Ti wars against the Mongols. According to his family records, he was seven feet tall, had a waist that was five feet in circumference, glaring eyes, and a stentorian voice.

Calicut’s incorporation in the Ming tributary system began in 1405 CE, according to port records (Chau Ju Kua – Chu Fan Chi), when the Zamorin’s envoys started making formal trips to China. Simply put, the tributary system was a method for ensuring that areas outside the empire had a place in the expansive Sinocentric universe. A document that acknowledged the foreign leader’s status as a tributary and formed a foreign policy with them was given to him as an imperial patent of appointment.

Chu Ti had ascended to the throne by force, thus the Emperor was particularly eager to establish and validate his legitimacy. Chu Ti commissioned the building of an imperial fleet in 1403 CE that was to contain commercial ships, warships, the fabled “treasure ships,” and support vessels because it was a time of immense wealth. It is thought that they transported big treasures to display Chinese wealth and might to the outside world. He then gave the order for the fleet, which was being led by Admiral Zheng He, to set off on a variety of lengthy journeys.

because Zheng Since he was Muslim, he would be able to build strong relationships with both Chinese and Muslim traders in the ports the ships frequented. Zheng During these expeditions, he allegedly oversaw a fleet of 317 ships, about 28,000 crew members, and their equipment and supplies. Between 1406 and 1433, he was in charge of seven different trips that made landfall in Calicut. The Ming dynasty built formal ties with various nations in South-East Asia, the Middle East, and India as multilateral trade flourished during this time.

Even though there is considerable debate regarding the size of these ships, they were rather enormous for the time. The search for the overthrown emperor Chien Wen, obtaining sizeable tributes from foreign nations, displaying Chinese might abroad, and fending off pirates from the South China Sea were some of the justifications for the costly voyages. Other reasons included support from Muslim nations to fend off the looming threat from Timur’s armies.

The Chinese sailors’ enormous ships caused a commotion when they arrived in Calicut. A Chinese Muslim scribe by the name of “Ma Huan,” who served as a translator for the fourth armada, which set sail in 1413 CE with 63 ships and 28,560 men, recorded information about some of Zheng He’s expeditions. The overall survey of the ocean’s shore is the title of the book (Ying-Yai Sheng-Lan).

Ma Huan wrote a lot about Calicut. He said, “This (Calicut, which in ancient Chinese was called Ku Li) is the great country of the Western Ocean.” In the fifth year of the Yung Lo, the court told the main envoy, the grand eunuch Zheng He, and others to give the king of this country an imperial mandate, a patent giving him the title of honour, and a silver seal. They were also told to promote all the chiefs and give them different grades of hats and girdles.

He also said, “The people are very trustworthy and honest. The way they look is smart, fine, and elegant. Foreign ships from everywhere come there, and the king of the country sends a chief, a writer, and others to watch the sales. Then, they collect the duty and pay it to the officials. Ma Huan also said that their musical instruments were “made of gourds with strings of copper wire, and the sound and rhythm were pleasant to the ears.”

In Calicut, what did the Chinese do? They went to Calicut and other places and, of course, bought goods and spices. But on each of the seven journeys, they also took time to fix the ships, rest, and get more supplies before moving on.

For the westward trade, they traded gold coins, spices from South-East Asia, and mostly rice from Odisha in Calicut to buy silver for the trip to Zanzibar. Chinese traders in Calicut bought medicine made from Arabian opium for a third of what it cost in Canton. This was another thing that Calicut merchants sold. As examples of goods, Ma Huan lists cloth, coconuts, and pepper. He also says that prices were set under a towel, which is still done in some wholesale shops today. He also talks about the Zamorins’ policy of passing power from mother to daughter, their religious practises, and the fact that a Chinese captain put up a stone stele in Calicut in 1409 CE to remember his trip there.

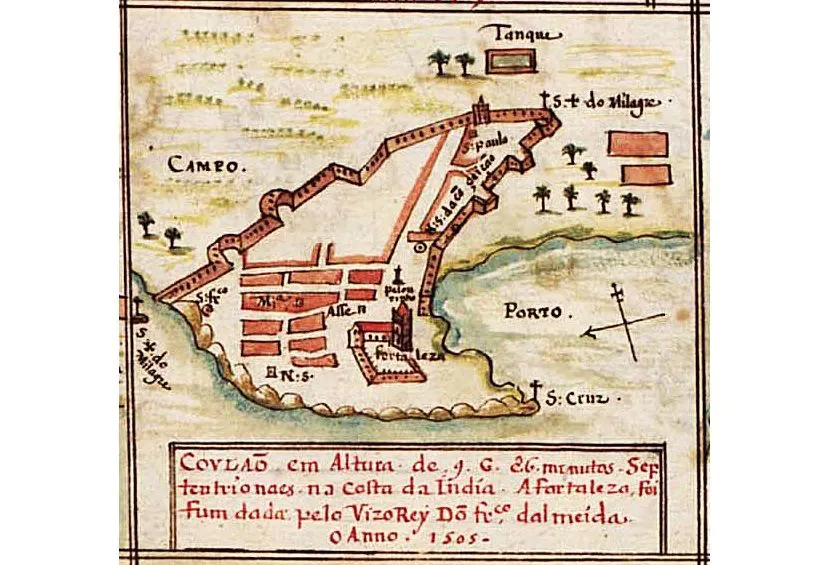

Where did the Chinese in Calcutta reside? They resided near to the Cheena Kotta, a fortified factory, in the vicinity of what is now known as Silk Street. This region was subsequently occupied by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the English (according to toponymic research, the Portuguese fort was also located nearby). Portuguese scribes noted the existence of another Portuguese fort and a small Chinese fort – Chinna Kotta – near Chaliyam (three to four miles south of Calicut), indicating the presence of a Chinese settlement. In those days, the two primary ports of Calicut were located at the estuary of the river Kallyi and at Pantalayini Kollam (three to four miles north of Calicut). Ceramic fragments unearthed during excavations indicate the existence of a Chinese settlement at Pantalayani Kollam, and according to Dr. Raghava Varier, this mediaeval port served as the Chinese ship repair centre. At Pantalayani Kollam, they had a Cheena Palli, which was their own mosque.

With the Mongol menace on its borders and the high cost of constructing defences, China’s situation deteriorated rapidly. The situation was complicated by floods, famines, and the pandemic. Chu Ti swiftly implemented a series of austerity measures after the state’s coffers ran exhausted. In 1421 CE, all sea travel was halted, along with the importation of luxury goods and the procurement of horses and teak wood.

To make matters worse, the imperial sponsor, Emperor Chu Ti, passed away in 1424 CE. After the new emperor seized power, the naval fleet was grounded, the crew was drafted into the army, and Zheng He and his teams were tasked with repairing the Nanking palaces. In 1431 CE, however, a final expedition set sail to recruit new envoys, returning three years later after visiting new locations in Africa, the Middle East, and Jeddah.

Zheng He presumably perished at Calicut during the final voyage of 1433 and was buried at sea. The Chinese economy continued to decline, and their difficulties in Annam (Central Vietnam) intensified. In the north, the Chinese were defeated by the Mongols, and the Ming ruler was captured. Ming China subsequently closed its gates, ports, and coastlines, effectively isolating itself from the rest of the world.

The next account of the Chinese in Calicut comes from the Malayali cleric Joseph, also known as “Joseph the Indian,” who travelled to Lisbon, Portugal, in 1501 C.E. aboard Alvarez Cabral’s Portuguese fleet. His accounts were published between 1510 and 1520 CE, albeit with a few alterations by his interlocutors. Joseph stated that the Chinese had conducted first-rate business in Calicut due to their extraordinary vigour. He describes how trade flourished when White Chinese with long hair, fez, and head decorations were present in Calicut, and adds that the Chinese had a factory there between 1410 and 1420 CE.

What he says next is quite dramatic: “Having been insulted by the King of Calicut, they rebelled and gathered a large army before destroying the city of Calicut. From that time until the present, they have never come to trade in that location; instead, they go to Mailapet, the city of King Naisindo.” So, according to Joseph, the Chinese left Calicut after this massacre and shifted their base to Mailapet, on the eastern shores of India (somewhere near Chennai), leaving behind in Calicut a small colony of half-castes (referred to as ‘Chini-Bachagan’ in William Logan’s Malabar Manual and 14th-century Persian traveller Abd-al-Razzaq Samarqandi’s memoirs).

To analyse the reasons for the Chinese departure, we must also consider the trade relations between the Mamluks and Calicut. During the Ming voyage of 1431 CE, a few ships from Zheng He’s fleet sailed towards Red Sea harbours, alarming Jeddah’s merchants. After learning of Zheng He’s demise, the Chinese returned swiftly to Calicut, but Arab ire may have been aroused. As the Chinese ships were larger and more powerful, it is plausible that they could also destroy Mamluk trade connections. In addition, the majority of Chinese sailors and admirals were Muslims. It may have been an act of vengeance perpetrated by Arab merchants of Calicut who believed the Chinese were planning to seize control of the lucrative Jeddah trade route. Did they take preventative measures to expel the Chinese from Calcutta? Perhaps!

More anecdotal evidence of Chinese influence in the region exists. A coronation stone used when power changed hands in Cochin and Calicut, as well as mentions of wars waged over the stone, demonstrates that the Chinese had some influence over the warring rulers of Calicut and Cochin. According to Portuguese records, the stone was a gift from the Chinese and was inscribed with Chinese and Tamil characters, with the Tamil characters documenting a list of Calicut or Cochin’s previous rulers. Over time, the stone vanished, never to be seen again.

There are also mentions of a sailing community (the Chini Bachagan mentioned previously) among the descendants of the Chinese in Calicut, as well as individuals who intermarried with the Marakkar and Mappila populace. There are references to the combatant Chinali and the admiral Chinese Cutiale, both of whom served in the Marakkar fleet and fought against the Portuguese.

As a result, major overtures to Calicut and the Middle East came to an end by the 16th century CE as a result of Ming China closing its sea boundaries and the Chinese leaving Calicut. In the meantime, the Portuguese were aware of the situation and had made the decision to sail to Calicut themselves, commissioning Vasco da Gama to lead the expedition.

In the year 2007 CE, a Chinese researcher by the name of Liu Yinghua was combing through old manuscripts at Calicut University when he came across 15 Chinese coins that were being used to bind some palm leaf manuscripts together. The emperors Qianlong (1736-1795 CE), Jiaqing (1796-1820 CE), and Daoguang (1821-1850 CE) are credited with minting these coins, which turned out to be from a considerably later date. This suggests that Calicut and China maintained some kind of commercial relationship well into the second half of the 19th century, as evidenced by the fact that trade ties have been found between the two countries.

Silk Street and, more generally, the various cooking tools and vegetables used in Malayali kitchens that are said to have originated in China are the only things that remain as proof of Chinese settlement in Calicut in the modern age. The cheena chatti (wok), the cheeni mulaku (little green chillies), the cheeni avarakka (Chinese beans), the cheena pattu (silk), and the cheena bharani (porcelain pots) are some examples of cheena. In the archives, we also come across the common words cheena vala (which translates to “Chinese nets at Cochin”), cheena padakkam (which translates to “fire crackers”), and cheeni kanam (which translates to “anchorage ship”). Some people even claim that the dhoti worn in Kerala was referred to as a “cheenathe mundu.”

The Ming emperor who supported the Zheng He missions is popularly known as the Yongle Emperor. His personal name was Chu Ti (Zhu Di), and he is also referred to as the Yongle Emperor. Ma He, Sanbao, and Chung Ho are all other names that might be used to refer to Zheng He.