Mauryan Empire Establishment:

The Maurya Empire was founded in 321 B.C. by Chandragupta Maurya was a one-of-a-kind historical occurrence.

Particularly given that it was discovered shortly after Alexander’s victorious operations in North-West India in 327 B.C. – 325 B.C.

There is no agreement on the ancestry of the Mauryas. The Puranas depict them as Sudras and uprighteous, which is likely due to the Mauryas’ patronage of heretical groups.

Mauryan

Buddhist texts (for example, Mahavamsa and Mahavamshatika) have attempted to connect the Mauryan empire with the Sakya tribe to whom the Buddha belonged. Bindusara, Chandragupta’s son, is characterised in the Divyavadana as Kshatriya Murdabhishikta, or anointed Kshatriya.

According to Buddhist literature, the Mauryas came from an area rich in peacocks (Mayura in Sanskrit and Mora in Pali), therefore they were called as the Moriyas (Pali form of Mauryas). It is clear from this that the Buddhists were attempting to elevate Asoka and his predecessors’ social standing.

According to Hemachandra’s Parisisthaparvan, Chandragupta was the son of the chief of a hamlet of peacock-tamers (Mayura-Poshaka). The use of the terms ‘Vrishala’ and ‘Kula-hina’ for Chandragupta in Vishakadatta’s Mudrarakshasa certainly indicates that Chandragupta was a simple upstart of an unknown family.

Greek classical sources, such as Justin, depict Chandragupta Maurya as a lowly man, but do not specify his caste. The Vaisya Pusyagupta is mentioned as the provincial governor of the Maurya king Chandragupta in Rudradaman’s Junagarh Rock Inscription (150 A.D.). There is a mention to Pusyagupta being Chandragupta’s brother-in-law, implying that the Mauryas were of Vaisya descent.

To summarise, the Mauryas were of fairly humble ancestry, belonging to the Moriya tribe, and were unquestionably of a low caste.

Chandragupta Maurya (322–297 BCE):

In 321 B.C., Chandragupta Maurya ascended to the Nanda throne. At the age of 25, he dethroned the last Nanda ruler (Dhanananda). He was the protege of the Brahmin Kautilya, also known as Chanakya or Vishnugupta, who served as his advisor and adviser both in gaining and maintaining the kingdom.

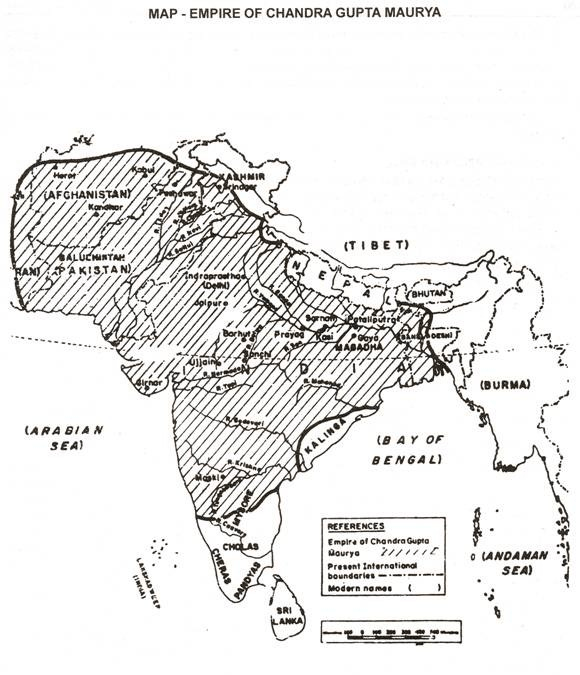

The conquest of Magadha was the first stage in the establishment of the new monarchy. Once he had control of the Ganges valley, Chandragupta headed to the north-west to exploit the power vacuum left by Alexander’s departure. He quickly seized control of the North West.

Returning to Central India, he occupied the area north of the Narmada River. But 305 B.C. saw him return to the north-west, where he was embroiled in a struggle against Seleucus Nikator (Alexander’s commander who acquired control of most of the Macedonian empire’s Asiatic territories), which Chandragupta eventually won in 303 B.C. Both parties signed a treaty and formed a marriage union.

It is unclear who married whose daughter. However, it appears that Chandragupta gave the Greek commander 500 elephants in exchange for the land across the Indus, including the Satrapies of Paropanisadai (Kabul), Aria (Herat), Arachoisa (Kandahar), and Gedrosia (Baluchistan). Megasthenes, Seleucus’ envoy, spent many years at the Maurya court in Pataliputra and travelled extensively throughout the country.

According to Jaina sources (Parisistaparvan), Chandragupta converted to Jainism near the end of his life and abdicated the empire to his son, Bindusara. He is reported to have travelled to Sravana Belgola near Mysore with Bhadrabahu, a Jaina saint, and several other monks, where he purposely starved himself to death in the accepted Jaina method (Sallekhana).

Arthashastra and Kautilya:

Chandragupta Maurya’s Prime Minister was Kautilya. With his assistance, Chandragupta established the Mauryan Empire. He wrote the book Arthashastra. It is the most essential source for writing the Mauryas’ history and is divided into 15 adhikarnas (parts) and 180 Prakaranas (subdivisions). It has approximately 6,000 slokas. Shamasastri discovered the book in 1909 and skillfully translated it.

It’s a book about statecraft and public administration. Regardless of its age and authorship, its significance stems from the fact that it provides a clear and methodical study of the Mauryan period’s economic and political conditions.

The similarities in administrative terms used in the Arthashastra and the Asokan edicts strongly suggest that the Mauryan rulers were familiar with this work. As a result, his Arthashastra provides useful and reliable information about the social and political conditions, as well as the Mauryan administration.

- King:

Kautilya advises that the king be an autocrat, concentrating all authority in his own hands. He should have complete control over his domain. At the same time, he should respect the Brahmanas and seek counsel from his ministers. As a result, the king, despite being an autocrat, must utilise his power prudently.

He should be well-educated and knowledgeable. He should also be well-read in order to comprehend all aspects of his administration. He claims that the king’s proclivity for evil is the primary reason of his downfall. He cites six evils that contributed to a king’s demise. They are arrogance, lust, rage, greed, vanity, and a desire for pleasures. According to Kautilya, the king should live in comfort but not indulge in pleasures.

- Kingship Ideals:

According to Kautilya, the main ideal of kingship is that his own happiness is dependent on the happiness of his subjects, and only happy subjects secure the happiness of their sovereign. He also claims that the monarch should be a ‘Chakravarti,’ or conqueror of other countries, and that he should gain honour by conquering other lands.

He must protect his people from external threats and maintain internal harmony. Before marching to the battlefield, Kautilya stated that the warriors should be instilled with the spirit of a “holy war.” Everything is fair in a war fought for the sake of the country, he claims.

- Concerning the Ministers:

Kautilya believes that ministers should be appointed by the king. A king without ministers is analogous to a one-wheeled chariot. The king’s ministers, according to Kautilya, should be wise and intelligent. However, the king should not become a pawn in their hands.

He should disregard their bad advice. The ministers should collaborate as a team. They should hold private sessions. He claims that a monarch who is unable to retain his secrets will not last long.

- Provincial Government:

According to Kautilya, the kingdom was split into regions that were controlled by members of the royal family. Other officers known as ‘Rashtriyas’ administered lesser provinces such as Saurashtra and Kambhoj. The provinces were then subdivided into districts, which were further subdivided into villages. The top administrator of the district was named the ‘SthaniK while the village headman was called the ‘Gopa’.

- Administration of Citizenship:

The administration of major cities, as well as Pataliputra’s capital city, was carried out quite efficiently. Pataliputra was split into four sections. The commander in charge of each area was referred to as the “Sthanik.” He was helped by junior officers known as ‘Gopas,’ who were in charge of the welfare of 10 to 40 families. Another official known as the ‘Nagrika’ was in control of the entire city. There was a regular census system in place.

- Organisation of Spies:

According to Kautilya, the king should maintain a network of spies who would bring him up to date on the latest news and events in the country, provinces, districts, and cities. Other authorities should be kept under surveillance by the spies. Spies are needed to keep the peace in the land. Women spies, according to Kautilya, are more efficient than men, hence they should be recruited as spies in particular. Above important, rulers should dispatch agents to surrounding countries to obtain political information.

- Shipping:

Another important piece of information we gained from Kautilya is on seafaring under the Mauryas. Each port had an officer who kept an eye on ships and ferries. Tolls were imposed on commerce, travellers, and fishers. The rulers owned almost all ships and boats.

- Economic Situation:

According to Kautilya, poverty is a key cause of rebellions. As a result, there should be no shortage of food and money to acquire it, as it causes discontent and ultimately undermines the king. As a result, Kautilya encourages the monarch to take actions to ameliorate his people’s economic situation. According to Kautilya, the main source of income in villages was land revenue, whereas the main source in cities was sales tax.

Bindusara (c. 297–272 B.C. ):

Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara in 297 B.C., who was known to the Greeks as Amitrochates (Sanskrit, Amitraghata, the destroyer of opponents). Bindusara led a campaign in the Deccan, pushing Mauryan control as far south as Mysore.

He is supposed to have conquered “the land between the two seas,” referring to the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. However, Kalinga (modern Orissa) on the eastern coast remained hostile and was subdued by Bindusara’s son Ashoka in the subsequent reign.

Bindusara maintained his father’s favourable relations with the Hellenic west in foreign affairs. He is supposed to have had ties with Antiochus I Soter, son of Seleucus Nikator, king of Syria, whose ambassador, Deimachos, is said to have been at his court.

As a man of many tastes and interests, he requested that Antiochus I send him some sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist; the latter, however, could not be delivered because it was not intended for export. Pliny describes Ptolemy Philadelpus of Egypt sending Dionysius to India as his ambassador. According to the Ashokavadana, an uprising occurred in Taxila during the reign of Bindusara, when the citizens rebelled to the persecution of the higher rulers. Bindusara dispatched Asoka to quell the insurrection, which he did successfully.

Ashoka (B.C. 268-232):

Bindusara died in 272 B.C. This resulted in a fight for succession among his sons. It lasted four years and ended in 268 B.C. Ashoka was successful. According to Asokavadana, Subhadrangi was Ashoka’s mother, and she was the daughter of a Brahman from Champa.

The Divyavadana version mostly corresponds with the Ashokavadana version. Janapadakalyani, or Subhadrangi in another rendition of the same text, is her name. Vamsatthapakasini, the Queen mother, is referred to as Dharma in Ceylonese sources.

According to mythology, Ashoka was handed the Viceroyship of Ujjain as a young prince. According to Buddhist sources, an insurrection occurred in Taxila during the reign of Bindusara, and Ashoka was dispatched to put it down. He did this without alienating the locals. This is supported by an Aramaic inscription from Taxila that mentions Priyadarshi, the viceroyal governor.

During his Viceroyalty of Ujjain, he fell in love with Devi, the daughter of a Vidisa merchant, also known as Vidisamahadevi or Sakyani. Karuvaki and Asandhimitra were two additional well-known queens of Ashoka. Karuvaki, the second queen, is recorded in the Queen’s Edict etched on a pillar at Allahabad, which mentions her religious and charitable contributions. She is named as the mother of Prince Tivara, Asoka’s only son whose name appears in the inscription.

In terms of Ashoka’s ascent to the throne, sources generally agree that Ashoka was not the crown prince but succeeded after killing his siblings. However, there is no agreement in the scriptures on the nature of the struggle or the number of his brothers.

The Mahavamsa says Asoka killed his oldest brother to become king, yet elsewhere in the same source, as well as in the Dipavamsa, he is believed to have killed ninety-nine brothers. According to the Mahavamsa, although Asoka executed ninety-nine brothers, he spared the life of the youngest of these, Tissa, who was later made vice-regent (He retired to a life of religious devotion after coming under the influence of the preacher Mahadhammarakkhita and was then known as Ekaviharika). Although there was a struggle, it appears that many depictions of it are simply exaggerations.

According to Taranatha, after attaining to the throne, Ashoka spent several years in pleasure pursuits and was so given the name Kamasoka. This was followed by a period of intense evil, earning him the moniker Candasoka. Finally, his conversion to Buddhism and subsequent piety earned him the moniker Dhammasoka.

The most significant event of Ashoka’s rule appears to have been his conversion to Buddhism following his victory over Kalinga in 260 B.C. Kaling controlled the land and sea access to South India, hence it was important for it to become a part of the Mauryan Empire.

The 13th Major Rock Edict clearly portrays the horrors and sorrows of this conflict, as well as Ashoka’s great remorse. ‘A hundred and fifty thousand people were deported, a hundred thousand were slaughtered, and many times that amount perished,’ said the Mauryan emperor. It has previously been said that he was dramatically converted to Buddhism soon following the fight, with its concomitant horrors.

But this was not the case, and according to one of his inscriptions, the Bhabra Edict, it was only after more than two years that he became a passionate follower of Buddhism under the influence of a Buddhist monk named Upagupta.

He also declares his acceptance of the Buddhist creed, faith in the Buddha, Dhamma (the Buddha’s teachings), and the Samgha. In a letter written expressly for the local Buddhist clergy, he refers to himself as the ‘king of Magadha,’ a title he only uses on this occasion.

During his reign, the Buddhist church was reorganised with the Third Buddhist Council gathering in Pataliputra around 250 B.C. Mogalliputta Tissa presided over it, but the emperor does not mention it in his inscriptions.

This emphasises Asoka’s clear distinction between his personal support for Buddhism and his obligation as monarch to remain unattached and neutral in favour of any faith. The Third Buddhist Council is notable because it was the ultimate attempt of the more sectarianism-oriented Buddhists, the Theravada School, to expel both dissidents and innovators from the Buddhist Order.

It was also agreed during this Council to send missionaries to various parts of the subcontinent and to make Buddhism an actively proselytising religion.

In his 13th Major Rock Edict, Ashoka identifies several of his contemporaries in the Hellenic world with whom he exchanged diplomatic and other missions. Antiochus II Theos of Syria (Amtiyoga), grandson of Seleucus Nikator; Ptolemy III Philadelphus of Egypt (Tulamaya); Antigonus Gonatus of Macedonia (Antekina); Magas of Cyrene (Maka); and Alexander of Epirus (Alikyashudala) have been recognised.

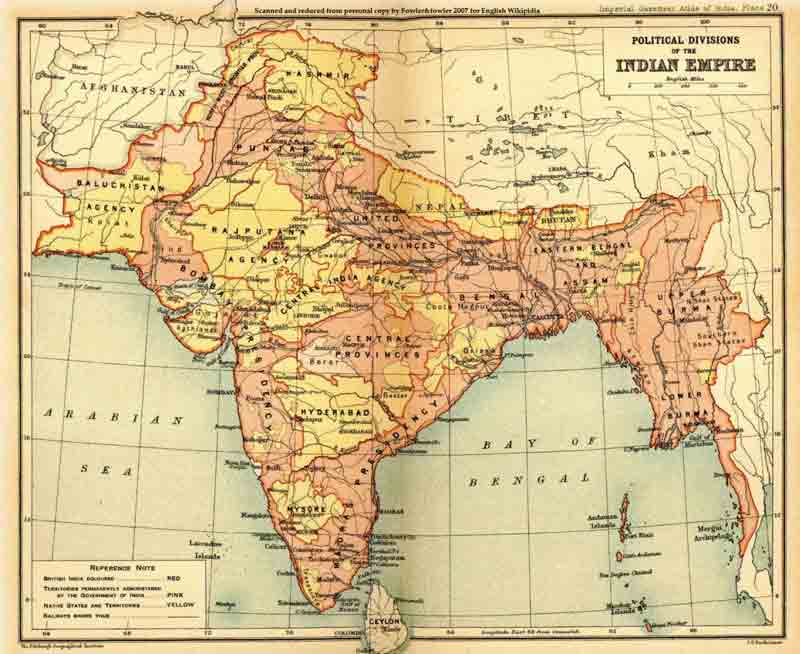

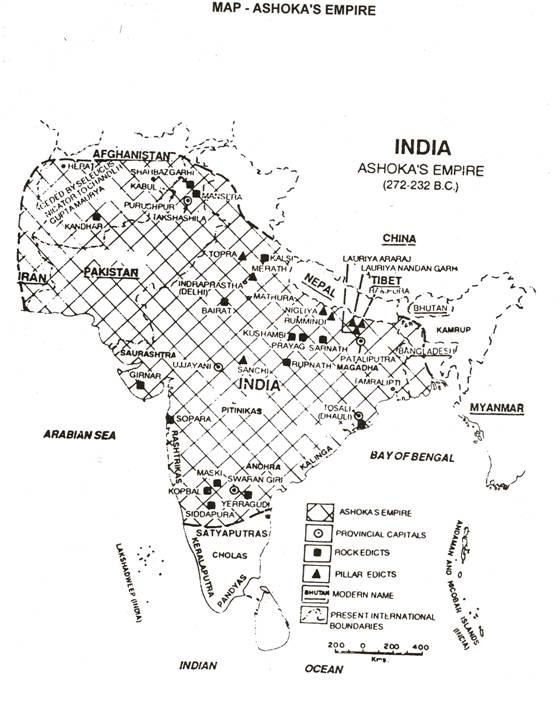

Communications with the outside world had advanced significantly at this point. The breadth of the Mauryan Empire can be estimated using Asokan inscriptions and archaeological data.

Magadha was the Mauryas’ home province, and Pataliputra was its capital. Ujjain, Taxila, Tosali near Bhubaneshwar, Kausambi, and Suvarnagiri in Andhra Pradesh are all mentioned in the inscriptions.

According to legend, Kashmir was part of the Ashokan Empire, and Ashoka founded the city of Srinagar. Khotan in Central Asia was likewise said to have fallen under Mauryan control.

Since the foothills were part of the Mauryan empire, the Mauryans had close ties with contemporary Nepal. One of Ashokan’s daughters is supposed to have married a mountain nobleman from Nepal.

Mauryan influence reached as far east as the Ganga delta. Tamralipti, or modern Tamluk, was a major port on the Bengal coast from which ships travelled to Burma, Sri Lanka, and South India. Broach, at the mouth of the Narmada, was another important port on the west coast.

Kandahar was the Mauryan Empire’s westernmost expansion, and Ashokan inscriptions list the Gandharas, Kambojas, and Yonas as his borderers. The Mauryas kept close communication with their neighbours, the Seleucid Empire and the Greek kingdoms, through the north-west.

The Mauryans had close links with Sri Lanka, and Asoka sent his son Mahindra and daughter Sanghamitra to promote Buddhism there. According to Asokan inscriptions in the south, he was amicable with the Cholas, Pandyas, Satiyaputras, and Keralaputras (Major Rock Edict II.)

The Empire’s Disintegration:

Asoka’s hold on the imperial organisation weakened at the conclusion of his reign. The Maurya Empire began to fall apart shortly after Asoka’s death in 232 B.C. The evidence for the later Mauryas is thin.

Aside from Buddhist and Jaina literature, the Puranas do contain some material on the later Mauryas, although there is no unanimity among them. Even within the Puranas, there is a great deal of variation from one to the next. The one point on which all Puranas agree is that the dynasty lasted 137 years.

Following Ashoka’s death, the empire was divided into western and eastern sections. The western section, encompassing the northwestern region, Gandhara, and Kashmir, was ruled by Kunala (one of Ashoka’s sons), and then for a while by Samprati (a grandson of Ashoka and a Jaina patron).

The Bactrian Greeks later besieged it from the north-west, and it was practically lost to them by 180 B.C. The Andhrasorthe Satavahanas, who eventually rose to power in the Deccan, posed a challenge from the south.

Dasaratha (possibly one of Ashoka’s grandchildren) governed the eastern section of the Maurya Empire, with its capital at Pataliputra. Apart from being described in the Matsya Purana, Dasaratha is also notable for the caves in the Nagarjuni Hills that he dedicated to the Ajivikas.

Dasaratha ruled for eight years, according to the Puranas. This would imply that he died without an heir of sufficient age to succeed to the throne. According to the same sources, Kunala ruled for eight years.

He must have died at the same time as Dasaratha, allowing Sampriti, who now rules in the west, to successfully reclaim the throne at Pataliputra, reuniting the empire.

This happened in 223 B.C. However, the empire had most likely already begun to fall apart. According to Jaina texts, Samprati reigned from Ujjain and Pataliputra. Salisuka, a prince referenced in the astronomical text, the Gargi Samhita, as a wicked quarrelsome king, came after Dasaratha and Samprati.

According to the Puranas, Salisuka’s successors were Devavarman, Satamdhanus, and lastly Brihadratha. The final prince was deposed by his commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra, who established a new dynasty known as the Sunga dynasty.

Causes of the Mauryas’ Decline:

After Ashoka’s death in 232 B.C., the Magadhan Empire, which had been raised through numerous wars culminating in the conquest of Kalinga, began to unravel. Historians’ explanations for such precipitous decreases are as contradictory as they are perplexing.

Some of the most evident and contentious reasons for the Mauryan Empire’s decline are mentioned below:

- The succession of weak monarchs following Ashoka was one of the more evident causes of the downfall.

- Another direct factor was the division of the empire into two parts, the eastern under Dasaratha and the western under Kunala. The Greek invasions of the north-west could have been pushed back for a while if the division had not occurred, allowing the Mauryas a chance to re-establish some of their prior authority. The division of the empire also caused problems with the various services.

- Scholars believe that Ashoka’s pro-Buddhist policies and his successors’ pro-Jaina policies alienated the Brahmins, leading to the uprising of Pushyamitra, the founder of the Shunga dynasty. H.C. According to Raychaudhuri, Asoka’s pacifist tactics were responsible for the empire’s demise.

The second theory holds Ashoka’s emphasis on nonviolence responsible for the empire’s decline and military strength. According to Haraprasad Sastri, the decline of the Mauryan Empire was caused by the Brahmanical insurrection in response to the ban on animal sacrifices and the loss of the Brahmanas’ status. Both of these arguments are overly simplified.

Pushyamitra’s throne takeover cannot be viewed as a brahmana revolution since the administration had become so ineffectual by that time that officials were eager to accept any plausible option.

The second proposition ignores the essence of nonviolent conflict resolution policy. Nothing in the Ashokan inscriptions suggests that the army was demobilised. Similarly, capital punishment was maintained. The emphasis was on reducing the number of species and animals killed for food. There is no evidence that animal slaughter has ceased entirely.

- Another rationale advanced by historians such as D.D. According to Kosambi, the Mauryan economy was subjected to significant strain under the later kings, resulting in high taxation.

This viewpoint is, once again, biassed and unsupported by archaeological evidence. Excavations at sites like as Hastinapura and Sisupalgarh have revealed advancements in material culture.

- The organisation of administration, as well as the conception of the state or country, had a significant role in the causes of the Mauryas’ decline. The Mauryan administration was highly centralised, necessitating a king with tremendous personal competence.

In such a case, a loss of central control automatically leads to a weakening of administration. With Ashoka’s death and the varied quality of his successors, there was a weakening at the centre, especially after the empire was divided.

- The Mauryan state acquired its finances from taxing a range of resources, which would have to grow and expand in order for the state’s administrative apparatus to be maintained.

Unfortunately, the Mauryas made little attempt to increase revenue or reorganise and reorganise resources. When combined with other causes, the Mauryan economy’s intrinsic weakness led to the demise of the Mauryan Empire.

- The extension of Gangetic basin material culture to remote places resulted in the development of new kingdoms.

Kanvas and Sungas:

The Mauryas were defeated in 180 B.C. For the time being, Indian history has lost its unity. Political events in India became more dispersed, involving a wide range of kings, eras, and people. While the inhabitants of the peninsula and south India were attempting to define their identities, northern India was caught up in the tumult of events in Central Asia. It was the second century B.C. The subcontinents were divided into a variety of governmental regions, each with their own goals. Sungas (c. 185-73 B.C.)

The Sungas, who are typically recognised as a Brahmana family belonging to the Bharadvaja clan, were the direct successors of the Mauryas in Magadha and the adjoining regions, according to the Puranas. The Sungas were officials under the Mauryas and originated from the province of Ujjain in western India.

Many details concerning the Sungas can be found in the GargiSamhita, Patanjali’s Mahabhashya, Divyavadana, Kalidasa’s Malavikagnimitra, and Bana’s Harshacharita. Inscriptions from Ayodhya, Vidisa, and Bharhut, as well as coinage discovered in Kausambi, Ayodhya, Ahichchhatra, and Mathura, illuminate the later Sunga history.

Pushyamitra Sunga lived between 185 and 149 B.C.

Pushyamitra, a general of the final Mauryan ruler Brihadratha, usurped the throne by slaying his master, founded the Sunga dynasty. He did not accept regal titles and was known as Senapati, or general, during his rule. Pushyamitra was an orthodox brahmanical believer who restored ancient Vedic rites such as the horse sacrifice.

According to Buddhist literature, he was a persecutor of Buddhists and a destruction of their monasteries and places of worship, particularly those founded by Ashoka. This was clearly an exaggeration, as archaeological evidence shows that Buddhist structures were being renewed at the time.

Despite being a regicide, Pushyamitra deserves credit for preserving the Magadhan Empire against the Bactrian Greek invasion and restoring some of its former power and glory.

He carried out two Asvamedha sacrifices (Ayodhya inscription), during which his courageous grandson Vasumitra saved the sacrificial horse from the Yavanas (Greeks) after a fierce fight on the Sindhu River’s banks.

Pushyamitra died around 149 B.C. After a 36-year rule, he was succeeded by his son, crown Prince Agnimitra, who had administered the southern regions during his father’s tenure. Agnimitra reigned for eight years. He is the protagonist in Kalidasa’s Malavikagnimitra.

Agnimitra was followed by inept successors. Bhagvata, the same as King Bhagabhadra of the Besnagar Pillar inscription, was a renowned Sunga King. Heliodorus was sent to his court as an ambassador by the Greek King Antialkidas.

It not only reveals the Sungas’ strong association with the Indo-Greek kings, but also the vitality of Indian culture when Heliodorus converted to the Bhagvata faith. Bhagvata was succeeded by Devabhuti, who was deposed in 75 B.C. by his Brahmin minister Vasudeva, who established the Kanva dynasty.

The Sungas Rule’s Importance:

- The Sungas fought in several wars. They fought against the Vidarbha (Berar) kingdom in the northern Deccan. They fought the Greeks in the north-west. The Sungas ruled the entire Gangetic valley, all the way to the Narmada River. The Sunga kingdom contained the cities of Pataliputra, Ayodhya, Vidisha, Jallandur, and Sakala (Sialkot).

- Pataliputra continued to be graced by the sovereign’s presence, but it had a rival at Vidisha, contemporary Besnagar in Eastern Malwa, where the crown prince Agnimitra held court.

- The Sunga period heralded a new era in architectural design. The huge stupa of Sanchi was expanded during the Sungas, and the railings that surround it date from the Sunga dynasty. The Bharhut railings have immortalised the Sunga period.

- Patanjali, who was born in Gonarda, central India, was a contemporary of Pushyamitra, and he mentions in his Mahabhasya that he officiated at one of Pushyamitra’s sacrifices.

Kanvas (73 – 28 B.C. ):

After slaying the king Sunga Devabhuti, the minister Vasudeva took the throne and established a new royal dynasty known as the Kanva or Kanvayana in Magadha. Bhanumitra, Vasudeva’s successor, was succeeded by his son Narayana. Susarman, Narayana’s son, succeeded him. The Kanva dynasty had four monarchs who ruled for 45 years, according to the Puranas. According to the Puranas, the Kanvas were defeated by the Andhras or Satavahanas.

Good article

LikeLike