The term ‘architecture’ comes from the Latin word ‘tekton,’ which meaning builder. The study of architecture originated when early man began to construct his own dwelling.

Sculpture, on the other hand, derives from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word ‘kel’, which meaning ‘to bend’. Sculptures are little works of art that are either handcrafted or created with tools, and they are more concerned with aesthetics than engineering and measures.

Indian art and architecture have evolved throughout time. Indian architecture, as a reflection of space and time, has changed throughout ages. It is intimately related to its history, religion, culture, geography, and socioeconomic status. From the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation to British authority, the structures and sculptures tell their own story. The growth of Indian architecture and art reflects the rise and fall of large empires, the invasion of foreign rulers who eventually became indigenous, the convergence of many cultures and styles, and so on.

This development will be thoroughly described in this chapter, starting with ancient Indian architecture and progressing to present times. The whole chapter is broken into three pieces.

Indian architecture in ancient India.

Indian architecture in the mediaeval period

Modern Indian architecture.

INDUS VALLEY ARCHITECTURE

- Although art forms such as pottery, sculpture, and so on emerged in the ancient era, architecture in its current form has its origins in the Indus Valley civilisation, namely town planning.

- The Indus Valley Civilisation, also known as the Harappan Civilisation, spanned the period from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE and saw the construction of some of India’s first large structures.

- In the second half of the third millennium BCE, a thriving civilisation formed on the banks of the Indus River and extended throughout most of North-Western and Western India. This is known as the Harappan Civilisation or the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC).

- There are many notable sites of the Indus Valley civilisation, each having its own architectural traits and similarities. These places have thriving urban architecture. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, the two most important sites of this civilisation, are among the oldest and best instances of urban civic design.

- The fact that the Harappan civilisation was urban does not imply that all or even the majority of its settlements had an urban character. The bulk were really villages.

- Harappan sites varied greatly in size and function, ranging from large cities to small pastoral camps.

- The greatest settlements include Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Ganweriwala, Rakhigarhi, and Dholavira.

- The second tier of Harappan settlements includes moderate-sized sites ranging from 10 to 50 hectares, such as Kalibangan.

- Then there are smaller sites of 5-10 hectares, such Amri, Lothal, Chanhudaro, and Rojdi.

- Allahdino, Kot Diji, Rupar, Balakot, Surkotada, Nausharo, and Ghazi Shah are some of the many settlements with an area of less than 5 ha.

Features of Harappan Architecture and Town Planning

- Most sites split cities into two parts:

- Citadel: It is smaller and taller than the rest of the region, rising 40 to 50 feet above the ground, and is located on the town’s western side.

- Lower town: It is significantly bigger in size than the citadel, although it is located on a lower plain. It is located on the east side. It is split intowards like a chess board.

- Cities are parallelogramic and set out in a regular grid arrangement. The roads went in north-south and east-west directions and intersected at right angles.

- There was a large-scale usage of burned bricks of conventional proportions (4x2x 1) for the purpose of construction, which differed significantly from expectations due to the lack of stone structures.

- These bricks were plastered and waterproofed with natural tar or gypsum.

- Kutcha bricks were used in houses, whereas pucca bricks were used in bathrooms and sewers after being waterproofed with gypsum.

- The cities consisted of well-planned and thoughtful architectural features:

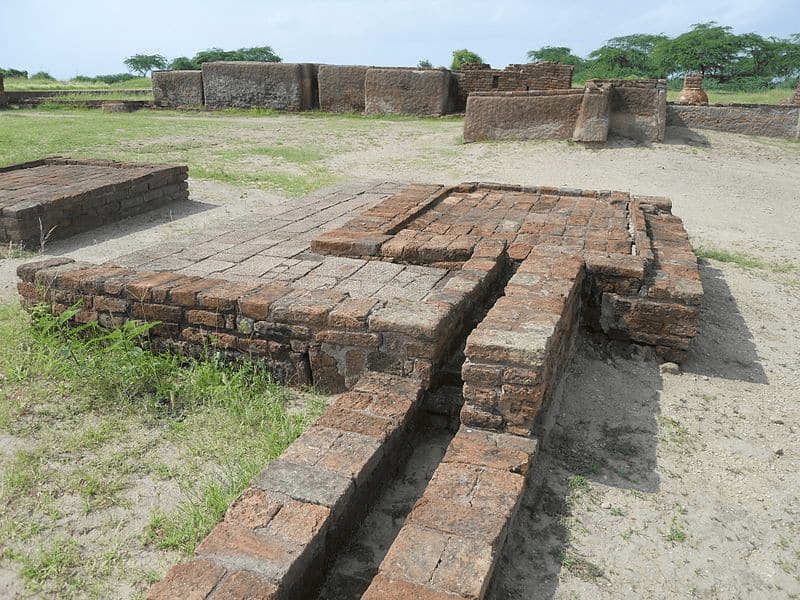

- Underground drainage with inspection holes – The drainage system is the most notable characteristic of this civilisation. Small drains went from each home and linked to major road drains. The inspection hole, which had a loosely connected top cover, was primarily for cleaning and maintenance. The photo below shows the drainage and dwellings. Cesspits were located at regular intervals. The emphasis on cleanliness, both personal and public, is extremely remarkable.

- The streets all ran from east to west or north to south.

- The Indus Valley city has vast walls and entrances around it, which served as protective barriers, showcasing the advanced architectural skills and strategic planning of its inhabitants.

- The walls may have been created to restrict commerce, prevent military invasion, and keep the city from flooding.

- Each component of the city had its own walled area. Each sector included a variety of structures, including public buildings, residences, marketplaces, and artisan enterprises.

- A brick wall surrounds the citadels of Mohenjodaro and Harappa.

- The citadels were walled, although it is unclear if they were defensive. They might have been created to redirect floodwater.

- At Kalibangan, a wall encompassed both the citadel and the lower city.

- In Sindhi communities such as Kot Diji and Amri, there was no city fortification.

- The location of Lothal in Gujarat has a totally distinct layout.

- The town was rectangular and enclosed by a brick wall.

- It did not have an internal division between citadel and lower city.

- An excavator discovered a brick basin along the town’s eastern edge, identifying it as a dockyard.

- Surkotada in Cutch was split into two equal portions, with mud bricks and lumps of mud serving as the primary construction materials.

- Harappan towns were believed to have grid-pattern streets and buildings orientated north-south and east-west.

- However, even Mohenjodaro does not exhibit a faultless grid layout.

- Roads in Harappan towns were not always perfectly straight or intersected at right angles.

- However, the settlements were definitely pre-planned.

- There is no clear relationship between the amount of planning and the size of a community.

- For example, the comparatively tiny site of Lothal has significantly greater levels of planning than Kalibangan, which is twice the size.

- There were covered drains on the road. Houses were erected along both sides of the highways and streets.

- Every street has a well-organised drainage system. If the drains were not cleaned, water flooded the dwellings and silt accumulated. The Harappans would then add another story on top of it. This boosted the city’s level over time.

- Obviously, this type of alignment of streets and residences shows purposeful town design. However, the resources available to municipal planners at the time were quite restricted.

- This notion is based on discoveries from Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan, where roadways stagger from block to block and street and building alignments in one region of Mohenjodaro diverge significantly from the others.

- Mohenjodaro did not consist of uniform horizontal units. In actuality, it was created at separate eras.

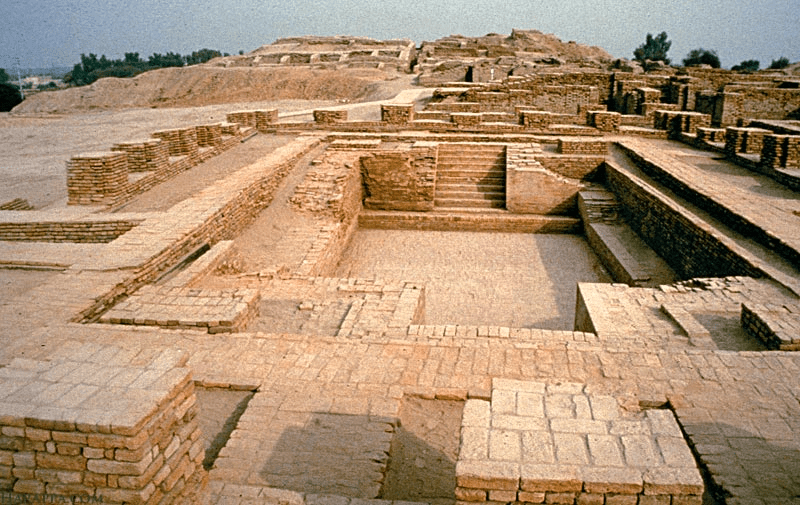

GREAT BATH : MOHENJODARO

- The citadel had a variety of facilities, including a great bath, pillared assembly rooms, and granaries.

- The Great Bath at Mohenjodaro has an amazing hydraulic system. It refers to the prominence of public baths and the significance of ceremonial cleaning in that age.

- The pool used to be in the midst of a vast open quadrangle surrounded by rooms on all sides. It connects to these rooms by a flight of stairs at each end. The pool was supplied by a local well, and the bad water flowed into the city’s sewage system via a massive corbelled drain.

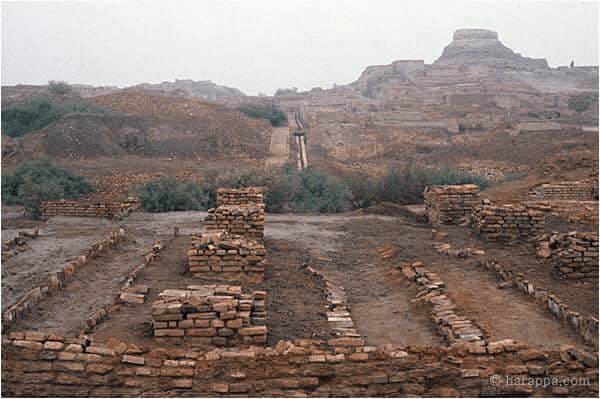

- Granaries: The granaries were created with strategic air ducts and high platforms, demonstrating the intellect behind their creation. The greatest structure in Mohenjodaro was the granary. Some sites, such as Harappa, have up to six granaries.

- Pillared Assembly Hall: The pillared hall, with twenty pillars grouped in five rows, most likely supported a massive roof. It might have functioned as the municipal magistrate’s court or the State Secretariat.

Pillared Assembly Hall

- The granary was the greatest construction in Mohenjodaro, whereas Harappa had around six granaries or storehouses. These were grain storage bins.

- Large granaries indicate that the state kept grain for ceremonial reasons and potentially to regulate grain output and sale.

- The granary of Mohenjodaro was unearthed in the citadel mound.

- It is made up of twenty-seven brick blocks connected by ventilation channels.

- Below the granary, there were brick loading bays from which grains were hauled into the citadel for storage.

- Though some academics have questioned the identification of this edifice as a granary, it is apparent that this massive structure had some vital purpose.

- Harappa’s Great Granary consists of brick platforms supporting two rows of six granaries.

- To the south of the granary, there were rows of circular brick platforms.

- The presence of wheat and barley chaff in the fissures of the flooring indicates that they were used for threshing grains.

GREAT GRANARY : MOHENJODARO

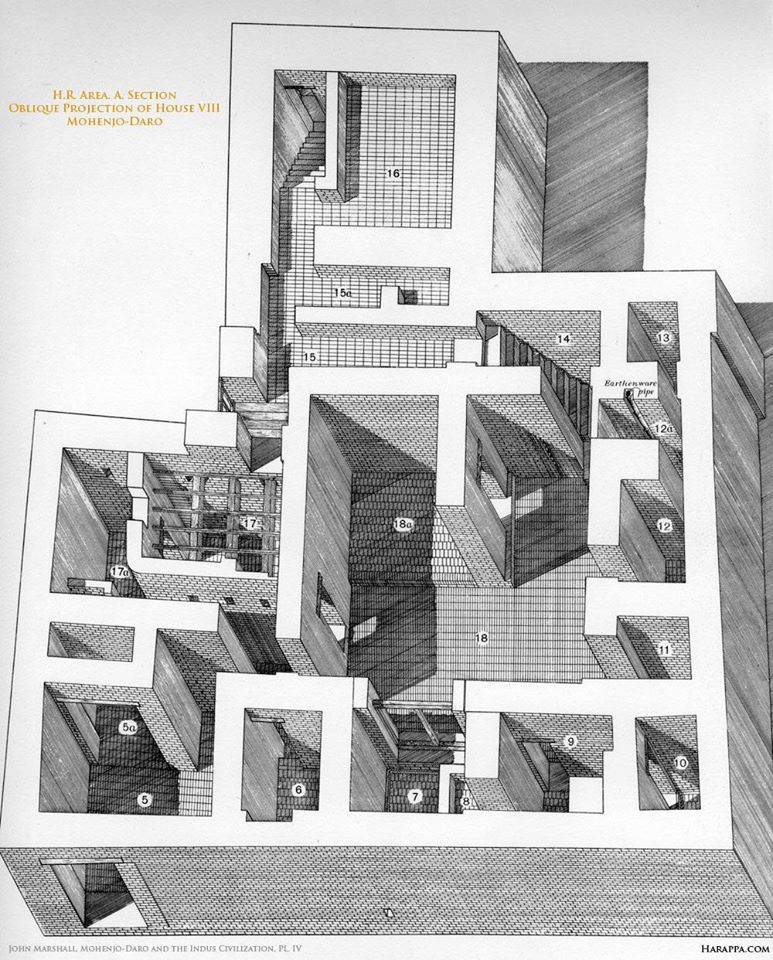

- The lower town featured houses of varying sizes, which some researchers suggest indicates a disparity in the economic status of its inhabitants. The societal divide between the affluent and the impoverished was evident in the presence of private wells and toilets among the wealthy.

- No residence featured windows that faced the main thoroughfare. The entrance to the house was approached from the side.

- The majority of structures exhibited adequate ventilation, despite the diversity in their designs, ranging from single-room edifices to multi-storied residences.

- The illustration presents a detailed layout of a residential structure.

HOUSING PATTERN

- Inhabitants resided in dwellings of varying dimensions, predominantly characterised by rooms organised around a central courtyard.

- The typical inhabitant appears to have resided in the residential complexes of the lower city.

- In this context, one can observe a diversity in the dimensions of the residences.

- It is possible that these are single-room tenements designed for enslaved individuals, akin to those unearthed in proximity to the granary at Harappa.

- Other residences were present, featuring courtyards and extending to as many as twelve rooms.

- In the more expansive residences, corridors extended into private chambers, and there exists substantial evidence of ongoing renovation endeavours.

- Larger residences typically featured a similar layout—a square courtyard encircled by several rooms.

- The larger residences or clusters of residences were equipped with distinct private wells, bathing facilities, and sanitation areas.

- Bathing platforms equipped with drainage systems were frequently situated in adjacent rooms to a well.

- The bathing area’s floor was typically constructed from closely arranged bricks, often positioned on their edges, to create a meticulously inclined and watertight surface.

- A diminutive drain extended from this point, traversing the house wall, and emerged onto the street, ultimately linking with a more substantial sewage system.

- It is plausible that diminutive residences adjoining more substantial ones served as accommodations for the service personnel employed by affluent urban inhabitants.

- Typically, doorways and windows orientated towards the side lanes, seldom revealing themselves to the main thoroughfares.

- The access points to the residences were situated along the narrow alleys that intersected the thoroughfares at perpendicular angles.

- The perspective from the lane into the courtyard was obstructed by a wall.

- The residence typically featured both an indoor and an outdoor kitchen.

- The outdoor kitchen would serve its purpose during warmer months to prevent the oven from raising the indoor temperature, while the indoor kitchen would be utilised in colder conditions.

- In contemporary times, the village residences in this area, such as those in Kachchh, continue to feature two kitchens.

- Staircases: Evidence exists of staircases that potentially provided access to the roof or an upper level.

- The presence of two-story houses or taller at Mohenjodaro is implied by the substantial thickness of their walls.

- Floors were typically constructed from compacted earth, frequently re-plastered or adorned with a layer of sand.

- The ceilings likely exceeded a height of 3 meters.

- Roofs could have been constructed using timber frameworks, adorned with layers of reeds and compacted clay.

- The entrances and apertures of residences were constructed from timber and woven materials.

- Clay representations of dwellings indicate that entrances were occasionally adorned or illustrated with rudimentary motifs.

- Windows featured shutters, potentially constructed from wood or reeds and matting, complemented by latticework grills positioned above and below to facilitate the entry of light and air.

- Several fragments of intricately carved alabaster and marble latticework have been unearthed at Harappa and Mohenjodaro; these slabs may have been integrated into the brickwork.

- Sanitation Facilities: While it is plausible that certain individuals resorted to the spaces beyond the city walls for their needs, numerous sites have indeed revealed the presence of designated sanitation facilities.

- The spectrum varied from the rudimentary excavation above a cesspit to more intricate configurations.

- Recent excavations at Harappa have revealed the presence of toilets in nearly every residence.

- The lavatories consisted of substantial vessels embedded in the ground, many of which were accompanied by a diminutive jar reminiscent of a lota, presumably intended for cleansing purposes.

- A majority of the pots featured a diminutive aperture at the base, allowing for the gradual percolation of water into the earth beneath.

- The effluent from the lavatories was, in certain instances, conveyed via an inclined conduit into a receptacle or drainage system situated in the thoroughfare beyond.

- It is likely that certain individuals were assigned the responsibility of maintaining the cleanliness of the toilets and drains on a consistent basis.

- The construction of houses in certain villages within the region continues to bear similarities to the architectural practices of the Harappans in various aspects.

Utilised raw material:

- A significant distinction between the structures in metropolitan areas and those in smaller towns and villages is in the variety and amalgamation of raw materials used.

- In villages, residences were mostly constructed from mud-brick, supplemented by mud and reeds; stone was sometimes used for foundations or drainage systems.

- Structures in urban areas were constructed with sun-dried and fired bricks.

- Baked bricks were used for construction at Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Mud bricks were used at Kalibangan.

- In the rugged regions of Kutch and Saurashtra, there was significant use of stone.

- The substantial fortress walls adorned with dressed stone at Dholavira, together with the remnants of stone pillars in the citadel, are unique and absent at any other Harappan site.

- The survival of some house walls at Mohenjodaro to a height of 5 meters attests to the durability of the bricks and the masonry expertise of the Harappans.

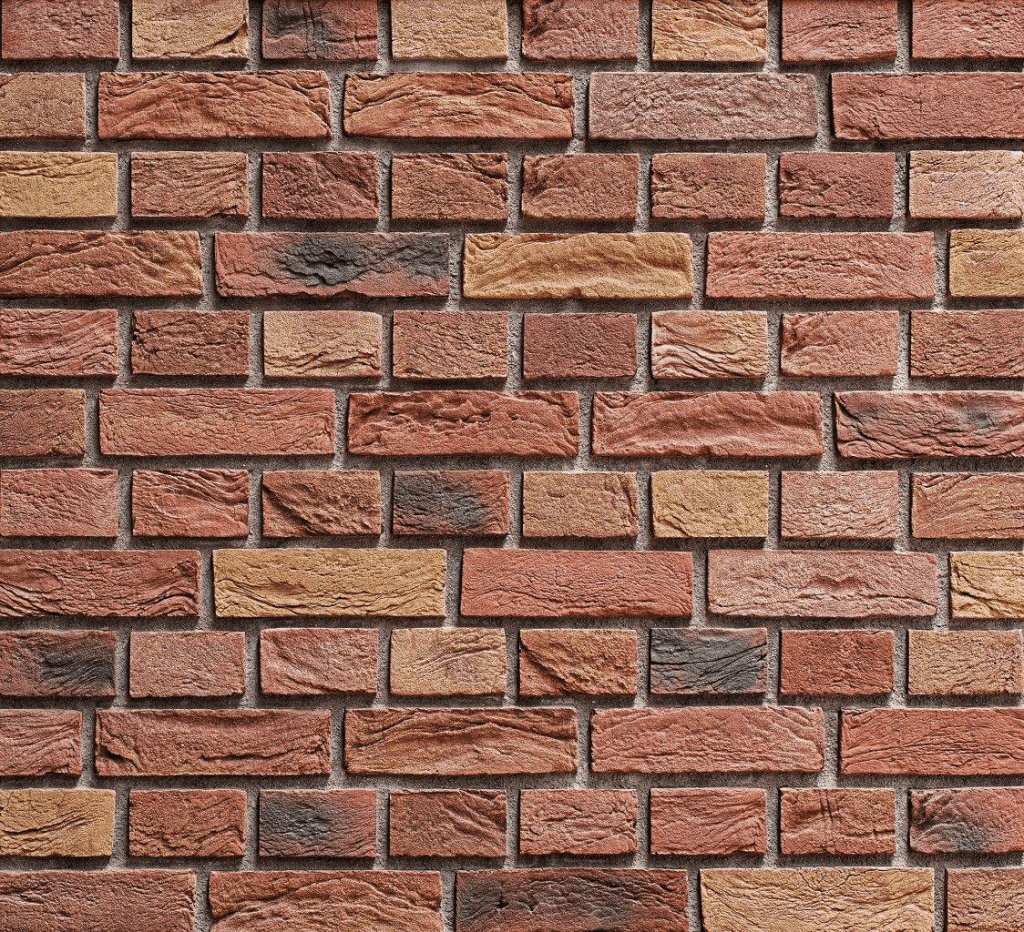

- Multiple bricklaying techniques exist, including the ‘English bond style.’

- Bricks were arranged in a pattern of long sides (stretchers) and short sides (headers), with an alternating configuration in successive rows. This conferred the wall optimal load-bearing capacity.

BRICK PATTERN : INDUS VALLEY

- A notable characteristic of Harappan architecture is the consistency in the average dimensions of the bricks — 7 × 14 × 28 cm for residential buildings and 10 × 20 × 40 cm for fortifications.

- Both these brick sizes have an identical ratio of thickness, width, and length (1:2:4).

- This ratio first appears at select locations during the early Harappan era, but is present in all settlements throughout the mature Harappan period.

- The uniformity of brick dimensions indicates that individual homeowners did not produce their own bricks; rather, brick manufacturing was conducted on a massive scale.

System for the Management of Water Resources:

- The drainage system exemplifies a remarkable aspect of Harappan settlements, characterised by its efficiency and meticulous planning.

- Even the lesser-known towns and villages boasted remarkable drainage systems.

- The systems designed for the collection of rainwater were distinct from the conduits and pipes utilised for sewage disposal.

- The construction of drains and water chutes from the second storey frequently involved their integration within the wall, culminating in an exit that positioned itself just above the street drain.

- At Harappa and Mohenjodaro, terracotta drain pipes efficiently channelled wastewater into open street drains constructed from baked bricks.

- Their convergence formed substantial drainage systems along the principal thoroughfares, which discharged their contents into the agricultural lands beyond the city walls.

- The primary drainage systems were elegantly concealed beneath corbelled arches constructed from either brick or stone slabs.

- Rectangular soakpits were strategically positioned at regular intervals to facilitate the collection of solid waste.

- It is imperative that these were maintained on a regular basis; failure to do so would have resulted in a compromised drainage system, posing significant health risks.

- Superb arrangements for sanitation reflect the existence of a civic administration that is prepared to make informed decisions regarding the sanitary needs of the entire community.

DRAINAGE PATTERN : LOTHAL

- The Harappans established intricate systems for the provision of water, catering to both drinking and bathing needs.

- The focus on ensuring access to bathing water, as observed at multiple locations, indicates a notable concern for personal hygiene standards.

- It is conceivable that regular bathing may have also encompassed a religious or ritualistic dimension. The origins of water included rivers, wells, and reservoirs or cisterns.

- The Great Bath at Mohenjodaro stands as a remarkable illustration.

- This edifice, constructed of brick, has dimensions of 12 meters by 7 meters and reaches a depth of approximately 3 meters.

- Access is granted from both ends via a series of steps.

- The base of the bath was rendered impermeable through the application of bitumen.

- A substantial well in a neighbouring chamber provided the water supply.

- A corbelled drain was also present for the purpose of discharging water.

- The bath was encircled by porticoes and an array of rooms.

- It is widely accepted among academics that the site served as a location for the ritual bathing of monarchs or religious leaders.

- Mohenjodaro is distinguished by its significant abundance of wells.

- In the ancient city of Mohenjodaro, it is posited that there existed over 700 wells.

- It was common for most residences or residential blocks to possess a minimum of one private well.

- A multitude of neighbourhoods featured public wells strategically positioned along the principal thoroughfare.

- Harappa featured a significantly reduced number of wells; however, a central depression within the city may indicate the presence of a tank or reservoir that catered to the needs of its residents.

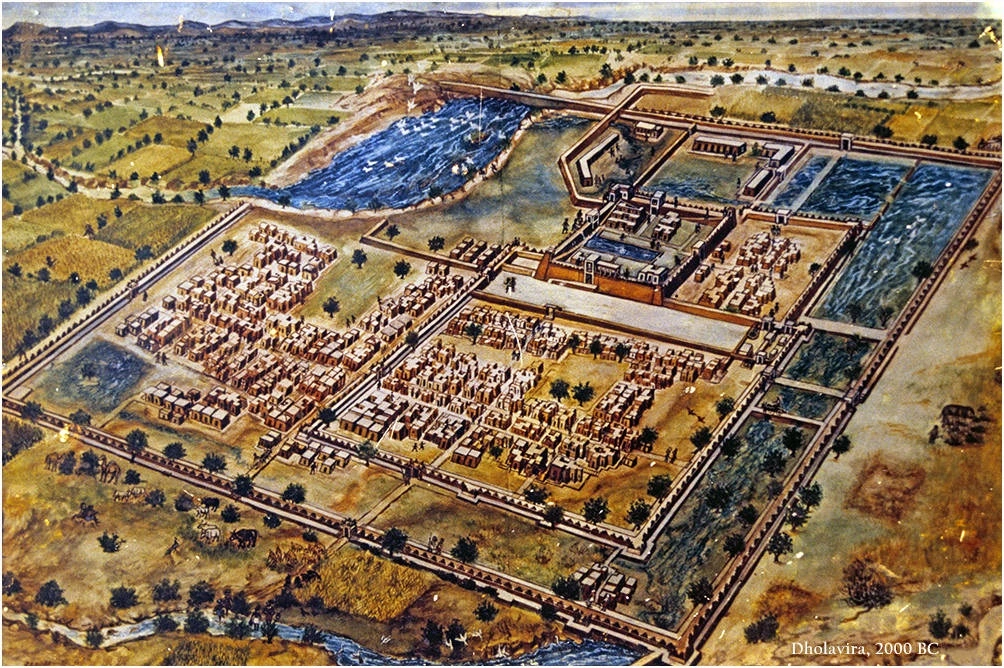

- Dholavira is distinguished by its remarkable water reservoirs, meticulously constructed with stone, although it does feature a limited number of wells.

- Dholavira had water storing tanks and step wells

DHOLAVIRA

Additional water management elements:

- In Allahdino, near Karachi, the wells possessed a small diameter, facilitating a higher rise of groundwater due to hydraulic pressure.

- It is possible that it was utilised for the irrigation of adjacent fields.

- Dholavira exhibited a remarkable and distinctive system for water harvesting and management.

- The water management system of Dholavira represents an architectural achievement that was essential in a region susceptible to recurrent droughts.

- Rainwater in the catchment areas of the two seasonal streams, Manhar and Mansar, was collected and redirected to the large reservoirs within the city walls.

- Numerous extensive, deep-water cisterns and reservoirs have been identified, which have retained valuable supplies of rainwater.

- There were 16 water reservoirs within the city walls, encompassing approximately 36 percent of the walled area.

- Brick masonry walls provided protection, while reservoirs were created by excavating the bedrock.

- The dockyard of Lothal represents the site’s most distinctive characteristic.

- The basin is approximately trapezoidal in shape and is enclosed by walls constructed of burnt bricks.

- The dockyard included mechanisms for sustaining a consistent water level through a sluice gate and a spill channel.

DHOLAVIRA : WATER RESERVOIR

LOTHAL : DOCKYARD

Many scholars argue that the Mesopotamian people of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley called Indus Valley civilisation as ‘Meluha’. Many Indus Valley seals have been found in Mesopotamia.

….To Be Continued

Follow us on Telegram @ plusstudents