Not only is Bengaluru’s Kempegowda International Airport the gateway to India’s silicon valley, but it is also the sole physical reminder, to those from outside the city, of the ruler who founded Bangalore in the 16th century CE. It is worth noting that the airport is in close proximity to Yelahanka, the capital of Kempe Gowda (1513–1570 CE). The Yelahanka Nadaprabhus, literally “Lords of the land of Yelahanka,” were his clan. Their capital was Hampi, and they were feudatories of the mighty Vijayanagara kingdom.

An inscription in the Parvathi Nageshwar Temple in Begur, thirteen kilometers from Bangalore, dates back to eight hundred and ninety-five CE and makes the first mention of Bengaluru. A “Bangaluru war” that occurred in 890 CE is mentioned on the inscription.

There is a story about the origin of the city’s name, as is typical in India. Legend has it that a local monarch got lost in this area once. He made a pit stop at a house where a woman fed him boiling beans; the neighborhood was later known as Benda-kaalu-ooru, meaning “Town of boiled beans”!

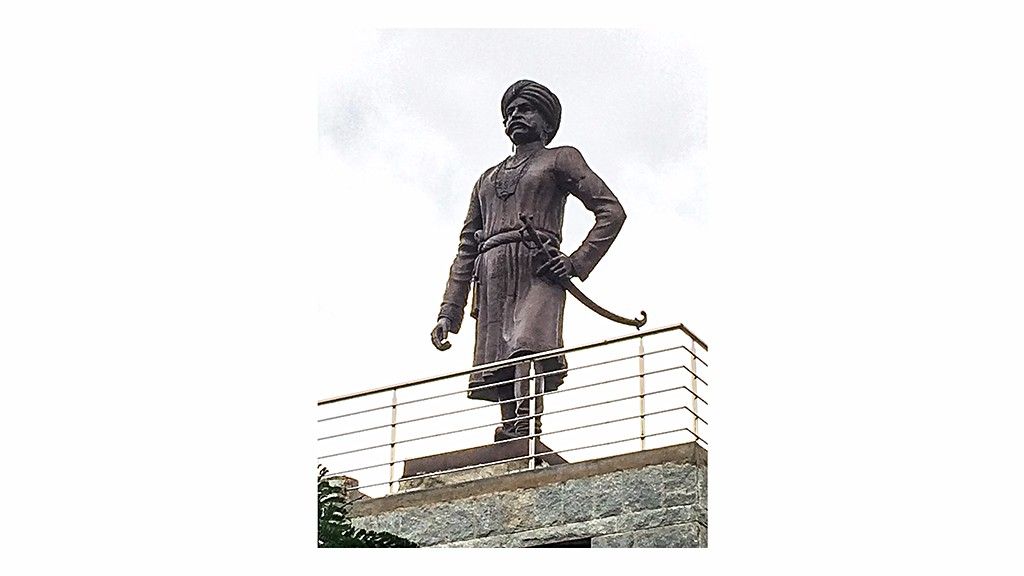

Statue of Kempe Gowda | Ashwin Raghunath

But according to history, the Yelahanka dynasty may be traced back to Devarasagowda (1230–1276 CE). He was a subordinate king to the Hoysalas, the ruling dynasty of the Yelahanka area. In 1310 CE, the capital of the Hoysalas, Dvarasamudra, was sacked by Malik Kafur, the general of Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khilji. This was only one of several assaults that the Hoysalas endured at the hands of the Delhi Sultanate. Following Harihara I’s foundation of the Vijayanagara empire in 1336 CE, the Yelahankas switched allegiances as well.

During Kempe Gowda’s reign (1513–1570 CE), the rulers of Yelahanka had fortified their ties to the Vijayanagara dynasty. The Vijayanagara king, Krishnadevaraya, bestowed the honorific “Chikkaraya,” meaning “little master,” to Kempe Gowda because of their close relationship. On top of that, he received a large bequest of 50,000 varahas, or gold coins, to construct a new city thirteen kilometers away from Yelahanka, which is now known as Bengaluru.

One of the old market (pette) in Bengaluru | Ashwin Raghunath

It is thought that Kempe Gowda extended an invitation to merchants and artists from all across the area to construct and reside in the city. They intended to build a stone fort with towers facing in each of the four directions. The deliberate layout and planning of this city as a “market city” emphasized the importance of business and set it apart from others. Part of the strategy was to set up specialized marketplaces, or “pettes,” for different industries. The construction of multiple similar pettes occurred between the 16th and 18th centuries CE. On the city map, you can still see some of these, like the Akkipete, Aralepete, Balepete, and Kumbapete.

Bangalore Fort | Ashwin Raghunath

However, difficulties arose throughout the construction of the city. According to urban legend, the fort wall continued to inexplicably crumble. Legend has it that Kempe Gowda dreamt that he would have to sacrifice a human being in order to make the gate permanent. It is reported that Kempe Gowda turned down Lakshmamma’s offer of self-sacrifice. But she supposedly disobeyed him and ended her life nevertheless. Reportedly, in the wake of this tragedy, Kempe Gowda erected a Lakshmi temple at Koramangala, a suburb of modern-day Bangalore, to honour her memory.

On the other hand, historians deny this account. The current-day Koramangala neighborhood, where the temple is located, was supposedly a sleepy little village when the temple was first built, making it an implausible site for such a monumental structure.

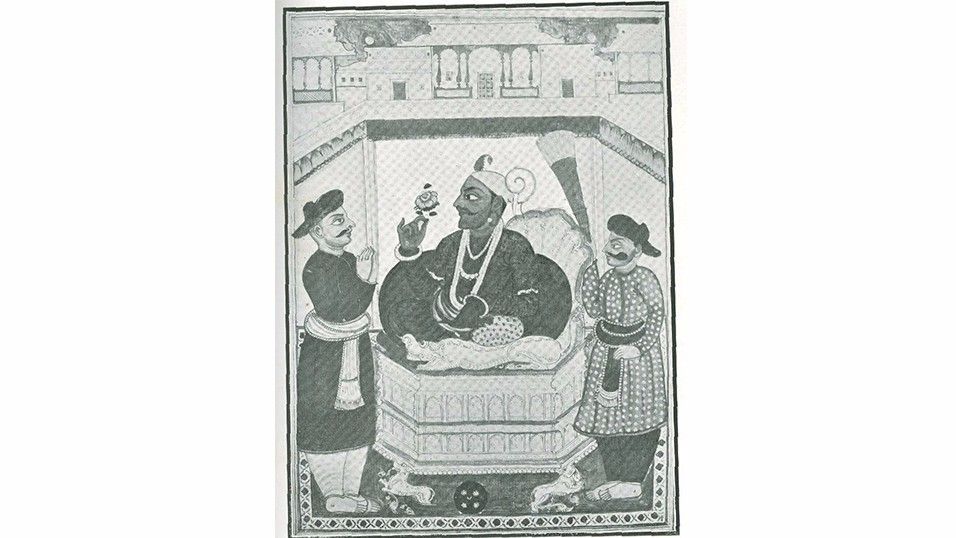

Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar | Wikimedia Commons

The Kempe Gowda family held sway over Bangalore from 1537 CE until 1638 CE. It was the administrative and military center as well as the capital. Nonetheless, in 1638 CE, when the Yelahanka chiefs’ authority waned, the town passed to the Maratha chief Shahaji Bhonsle, who happened to be the father of Chhatrapati Shivaji and had served in Adil Shahi’s army. Qasim Khan, general of Emperor Aurangzeb, led the Mughals to conquer the region later on.

In 1689 CE, Qasim Khan surrendered Bangalore to Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar, lord of Mysore under the Wodeyar family, for three lakhs. Despite losing its status as an administrative town, Bangalore continued to develop and grow throughout this time as a commercial hub.

Wodeyar King Immadi Krishna Raja Wodeyar rewarded Haider Ali, father of Tipu Sultan, with the jagir (gift) of Bangalore in 1759 CE for his victories against the Nairs of Malabar. In the years that followed, Bangalore was a political stronghold.

Tipu Sultan’s summer Palace | Wikimedia Commons

After Lord Cornwallis’s British East India Company captured Bangalore fort in 1791 and murdered Tipu Sultan in 1799 CE, the English ruled over this town. The town took on a new character by 1809, thanks to the British. A cantonment was built, roads were widened, and modern drainage systems were installed here. Because of this, the conventional markets, also known as pettes, became irrelevant. Residents of the Pettes actually began tearing down their homes and constructing shops in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries CE. Because of this, the ancient city’s walls and ditches were dismantled, paving the way for what is now known as the modern city.

The Madras Sappers continue to use the British cantonment, which was built in 1809 CE, as their headquarters.