Bengaluru is in the middle of the second wave of the Covid19 pandemic. This is a story of pain and hope. It’s a silver lining that has stuck around since a previous pandemic. The city changed from a medieval fort town to a contemporary city when the bubonic plague destroyed it in the late 1800s.

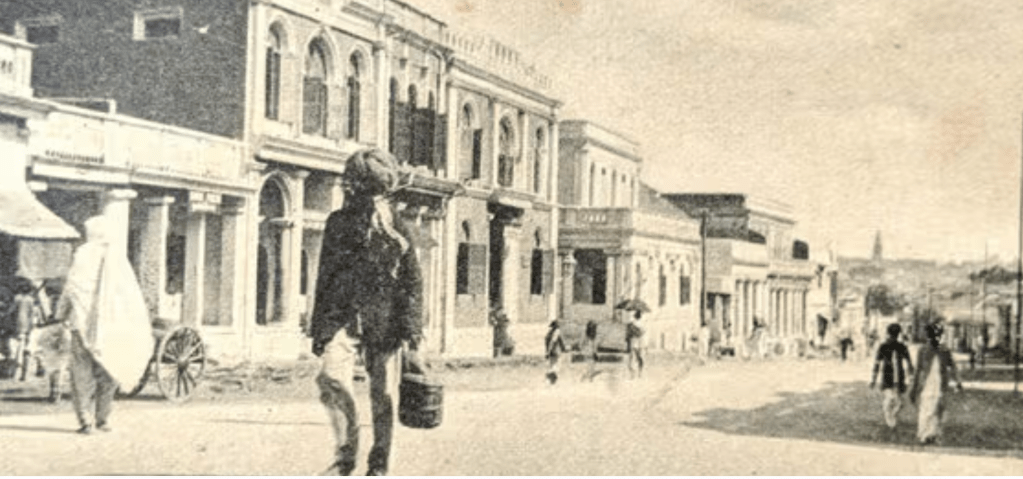

The British set up a cantonment at Bangalore in 1809, when the city was still part of the royal state of Mysore. This drew Europeans, Anglo-Indians, and Parsis to the city, although most of the original people resided in the “old city,” which was made up of areas called “pethes.”

Everything was OK until 1897, when deaths from the bubonic plague, which had spread to Bombay city, were found in portions of Bombay Province that are today part of Northern Karnataka. The colonial authorities quickly got ready for a pandemic. In addition to using the Epidemic Diseases Act II of 1897, it gave the Plague Fund Rs 2,45,970 and named the Inspector General of Police V P Madhav Rao as the Plague Commissioner.

But the epidemic nonetheless hit Bangalore, hitting both the city and the cantonment districts. The plague appears to have come in on a train from the Southern Maratha Railways. The train came from Bombay to Hubli and then to Bangalore Cantonment Station on August 11, 1898.

To be safe, the trains had started to physically check passengers and send a police officer with them to their destinations to keep an eye on their health. For ten days in a row, these passengers had to go in for health exams.

A railway loco superintendent and his butler were among the passengers who got off at the station. The butler showed signs of the epidemic a few days later. On August 15, 1898, the butler perished from the plague. The disease quickly swept throughout the city.

Within nine days following the first death from the plague, several cases were documented in the Goods Shed region. By August 24, twelve individuals had died. In the next several days, the number of plague cases rose, and by June 1899, the number of dead had reached 2,665.

Reports from the government say that 3,393 plague fatalities had not been reported, which means that the situation was far worse than thought. There were also a lot of deaths in the cantonment districts. Between September 1898 and March 1899, the plague killed 3,321 people here. People were scared all over. Workers at the hospital left their jobs and ran away, and so did the sweepers. The next year, there were 348 more fatalities from the plague in cantonment districts.

A lot of people left Bangalore city because of the epidemic and went to live in rural areas and small villages. The number of people living in Bangalore dropped from about 90,000 in 1898 to 48,236 by December 1899.

Historian Suryanath Kamath says that many portions of Bangalore became ghost towns because of empty streets and abandoned dwellings.

Life was awful for those who stayed behind. Prices of basic products went through the roof while people had no money since there was no work. The emotional toll was just as bad, since families had to leave behind sick relatives when they evacuated to safer places.

It was quite hard to get rid of bodies, and it was usual to see them lying around in empty places. They were sometimes thrown away in empty buildings, public restrooms, and even trash cans. People who worked to help often took bodies out of the gutters that were covered in mats or blankets. The authorities had to do something special to get rid of the bodies because people were too scared to give them last rites.

The pandemic not only killed people, but it also hurt the economy of what used to be a busy center of trade and business. Commercial activity came to a halt, and a lot of people couldn’t find work or buy food. A lot of households were poor since their breadwinners had died.

Rebuilding the City

Even while the epidemic caused a lot of problems, there was a bright side. The government knew that Bangalore’s infrastructure needed to be updated to keep a health disaster from happening in the future.

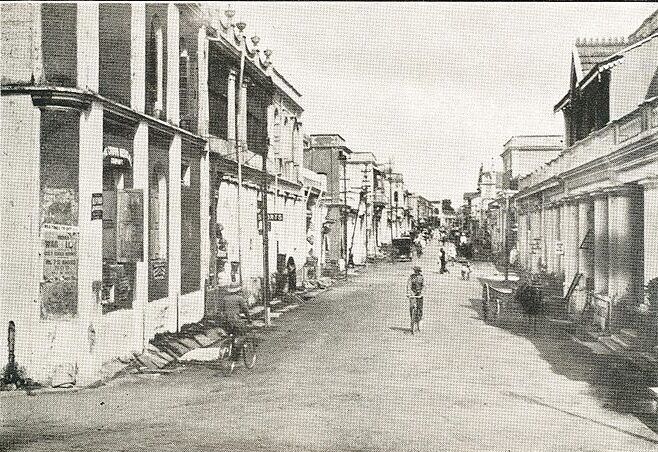

A precise strategy for the city’s growth was devised and put into action. In addition to reconstructing ancient neighborhoods, new, well-planned layouts were made, and people were urged to move to these regions. Basavanagudi, which covers 440 acres, and Malleshwaram, which covers 291 acres, became models for how to plan a town. They were new, with wide roads, a modern drainage system, green spaces, conservation roads, and other such features.

– Each home plot in these places was made such that a house could fit with enough open space for fresh air, sunlight, and clean drinking water.

These new neighborhoods nearly quadrupled the size of Bangalore, increasing the city’s total area from 500 acres to 1,123 acres. With these new plans, the government also started tearing down a lot of buildings to make the city less crowded and messy. So, in addition to 651 old, broken-down, and uninhabitable homes, 707 more buildings were torn down to make room for road expansion work. So, out of the 17,275 residences in the city, 1,356 were destroyed.

The government paid Rs 1 lakh to bring the city’s drainage system up to date. Disinfection on a large scale, spanning 8,113 homes, was done. The Health Department checked every house and found those that didn’t have enough ventilation. They then made sure that the roofs were either removed or drilled enormous holes in them to let air in! Regulations for building were set up and made required for all new buildings.

Modern Healthcare

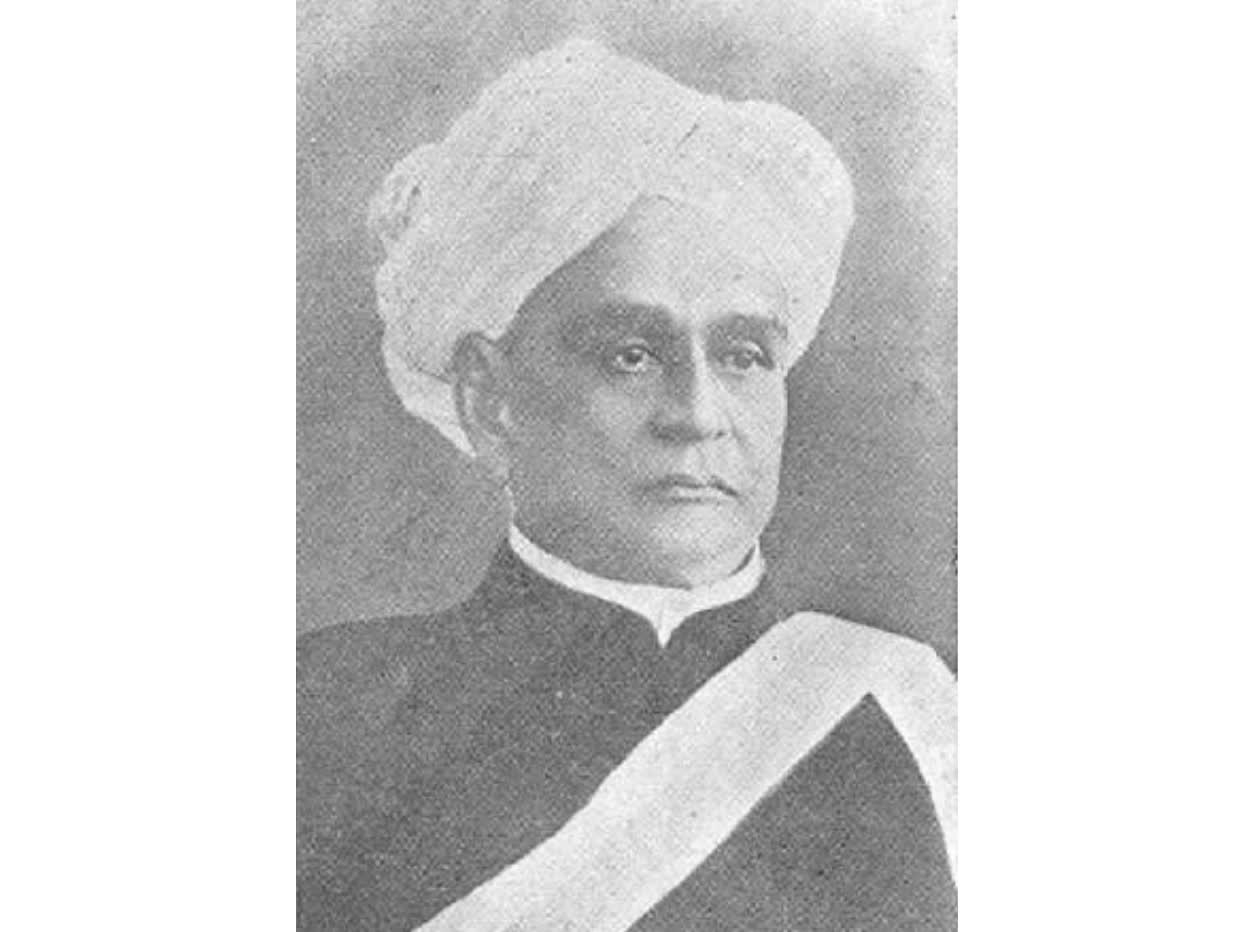

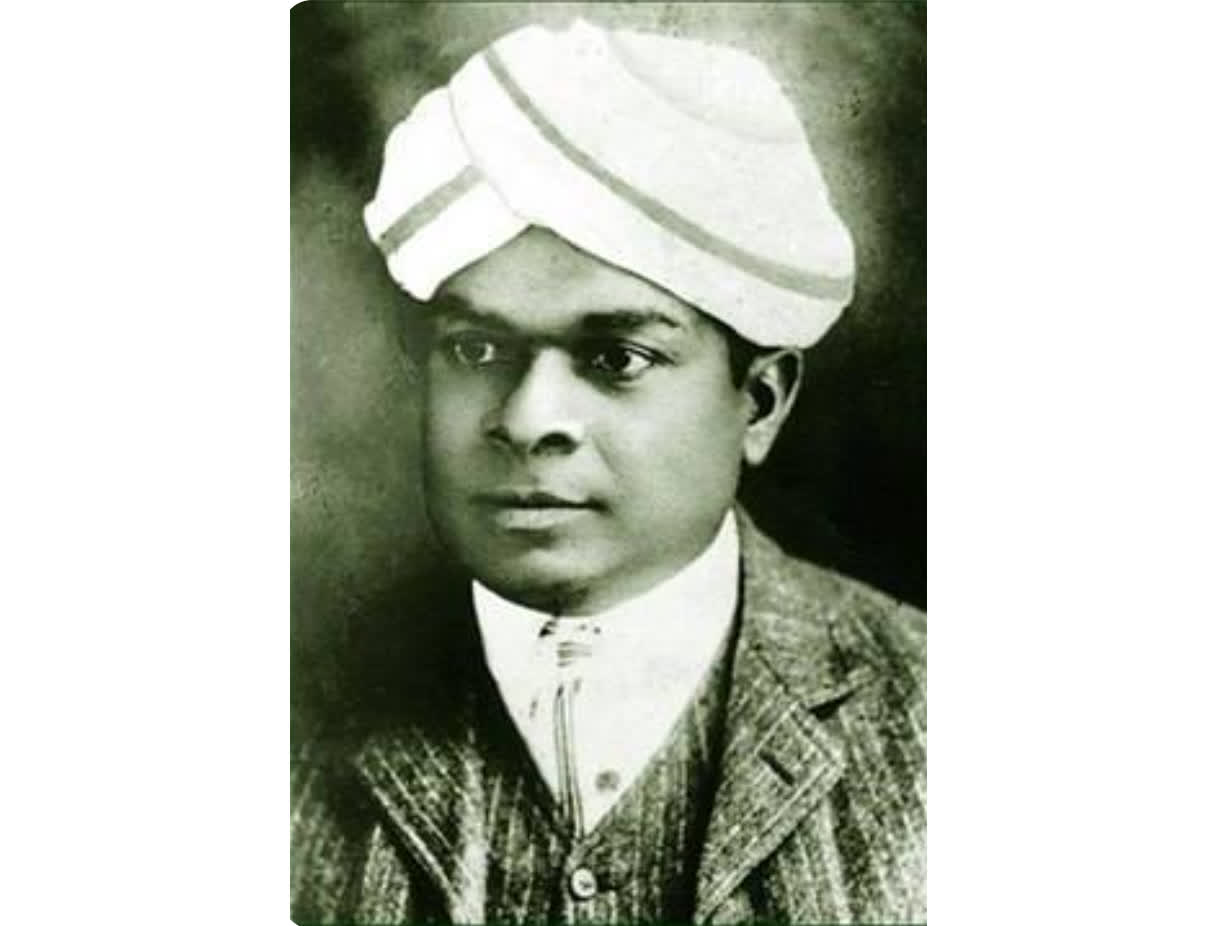

The state’s health care system also went through a big transformation. During the epidemic, the government hired Dr. Padmanabhan Palpu, a well-known doctor and bacteriologist who had trained in London, as the first Chief Medical Officer of Mysore State. He was paid Rs 400 a month. The government put him in charge of making health care facilities and medical infrastructure better since they were impressed with his amazing track record. He was a big part of turning the pandemic treatment center into a real plague hospital. He also helped build the state-of-the-art Victoria Memorial Hospital, which Lord Curzon opened in 1900.

Telephone Services

The bubonic plague is what gave Bengaluru its phone network. For the first time, the city set up a larger telephone network to help with plague management. In 1889–1900, the official report says that an average of 122 calls were made each day. Within a year, 50 government buildings were connected to the phone network. Also, the city’s modernization led to a lot of new businesses, such hotels, which opened in great numbers.

In 1906, Bangalore got electricity. By the 1920s, the city had a lot of new public buildings, parks, and layouts erected around it. Because of this, Bangalore was regarded as India’s “Garden City” until the 1990s.

Bengaluru is currently better known as India’s tech capital, the city that started the digital revolution there, than for its nice weather and high quality of life. But as the city adapts to meet new difficulties, let’s never forget how it came back from the dead after the plague and think about what we can learn from it.